Reading Corner: William Hamilton's Preface to Narrow Roads of Gene Land Volume 2

Or, what it is like to be a misunderstood aspie

Note: The “Reading Corner” series will consist of large excerpts from books, accompanied with a modest amount of commentary from me. The posts in this series are basically pointless, aside from allowing me to point at things I find interesting.

I have recently noticed that a solid majority of authors I am reading have been retroactively diagnosed with Asperger’s (or Autism Spectrum Disorder now). I don’t know what this says about me.

For instance Jeremy Bentham, the founder of utilitarianism, and subject of the essay “Asperger’s Syndrome and the Eccentricity and Genius of Jeremy Bentham”, was described thusly by John Stuart Mill:

…the incompleteness of [Bentham’s] own mind as a representative of universal human nature. In many of the most natural and strongest feelings of human nature he had no sympathy; from many of its graver experiences he was altogether cut off; and the faculty by which one mind understands a mind different from itself, and throws itself into the feelings of that other mind, was denied him by his deficiency of Imagination.

Derek Parfit later in life speculated that he had undiagnosed Asperger’s. Amia Srinivasan in her obituary for Parfit wrote:

Until a year ago, Derek read everything I wrote for publication, including my pieces for the LRB, and usually sent them back to me with detailed comments within a few hours. He would point me towards a relevant passage of Nietzsche, or suggest that a metaphor was too violent, or raise a fundamental philosophical objection. I wasn’t special to Derek; many philosophers, young and old, have similar stories. Sometimes I would pass by him in college and he would smile at me in a way that didn’t entirely convince me I was recognised.

I don’t think it’s unfair to say that Derek didn’t see what is obvious to many others: that there are persons, non-fungible and non-interchangeable, whose immense particularity matters and is indeed the basis of, rather than a distraction from, morality. But in not seeing this, Derek was able to theorise with unusual, often breathtaking novelty, clarity and insight. He was also free to be, in some ways at least, better than the rest of us. After he retired from All Souls, Derek didn’t like to go to the college common room, so we had our last meeting in my study. While jostling his papers he knocked over a glass. He was unfazed. We sat and talked for a few hours, his feet in a pool of water and shattered glass.

David Edmond’s new biography of Parfit contains many similar stories. Robin Hanson is a similar case.

This sort of speculative diagnosis is meant (unintentionally, I assume) to provide grounds for dismissing, at least partially, these thinkers’s ideas. Their ideas are a bit too alien, a bit too demanding, a bit too systematic; of use principally to people who need systems to do what their native intuition cannot, namely apprehending other people’s minds and intentions.

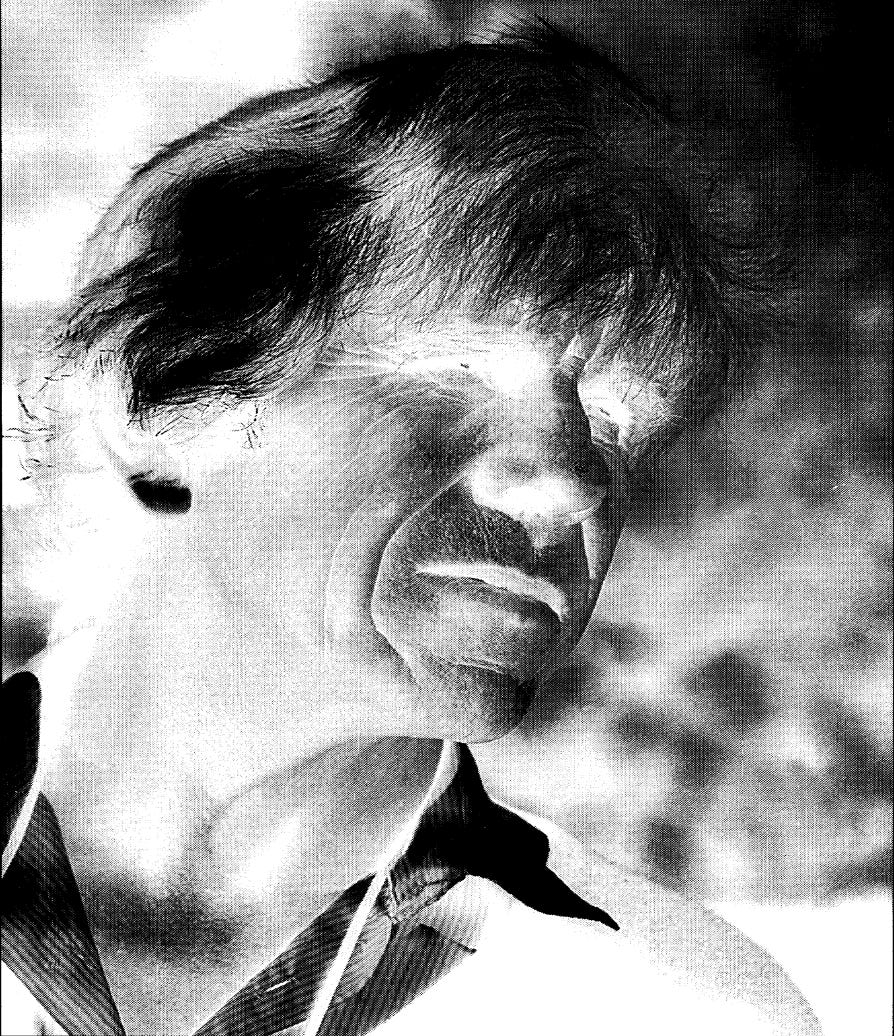

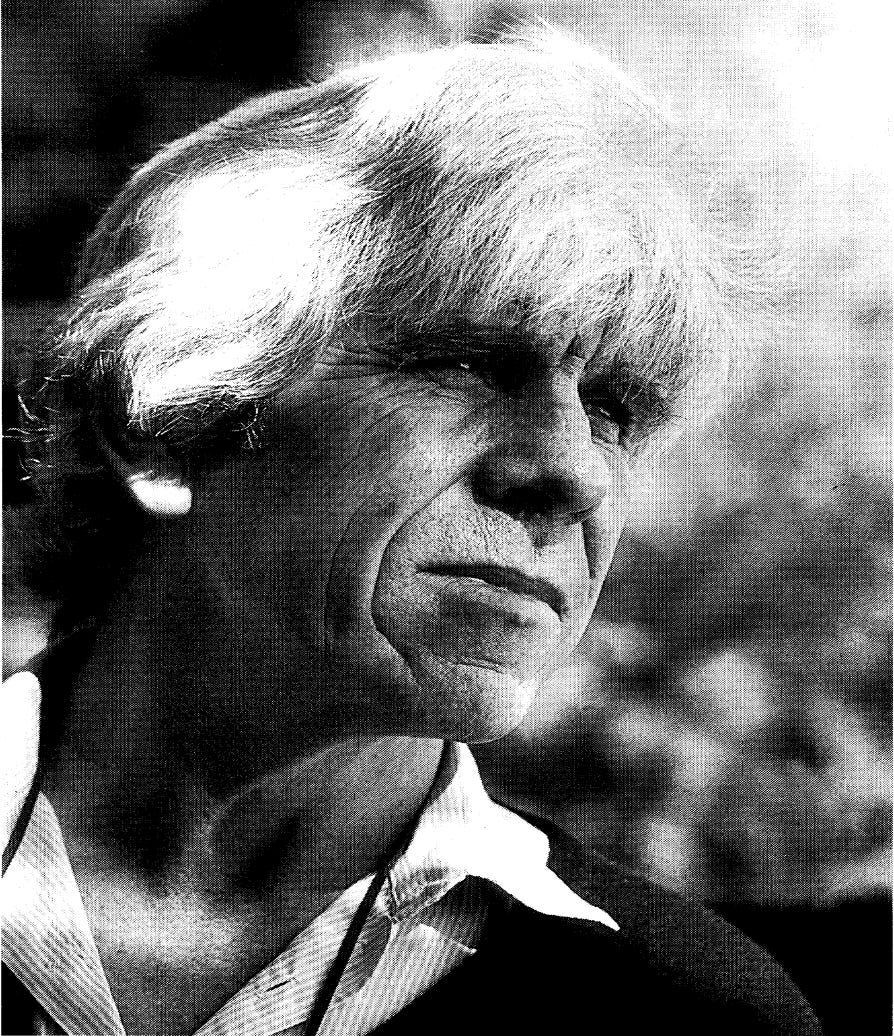

I have been reading the three volumes of William D. Hamilton’s Narrow Roads of Gene Land, which is a compilation of his papers and essays in evolutionary biology. I want to share here a long preface from Hamilton in the second volume, which gives a vivid depiction of what it is like being an aspie who is constantly accidentally giving offense. But before sharing that, I want to include some compelling anecdotes about the man affectionately written by Hamilton’s friend Richard Dawkins:

Every day he cycled into Oxford from Wytham, at enormous speed. So unbecoming was this speed to his great shock of grey hair, it may have accounted for his numerous cycle accidents. Motorists didn’t believe that a man of his apparent age could possibly cycle so fast, and they miscalculated, with unfortunate results. I have been unable to document the widely repeated story that on one occasion he shot through the windscreen of a car, landed on the back seat and said, ‘Please drive me to the hospital’. But I have found reliable confirmation of the story that his start-up grant from the Royal Society, a cheque for £15,000, blew out of his bicycle basket at high speed.

I first met Bill Hamilton when he visited Oxford from London, in about 1969 to give a lecture to the Biomathematics Group, and I went along to get my first glimpse of this man, who was already my intellectual hero. I won’t say it was a let-down, but he was not, to say the least, a charismatic speaker. There was a blackboard that completely covered one wall. And Bill made the most of it. By the end of the seminar, there wasn’t a square inch of wall that was not smothered in equations. Since the blackboard went all the way down to the floor, he had to get on his hands and knees in order to write down there, and this made his murmuring voice even more inaudible. Finally he stood up and surveyed his handiwork with slight smile. After a long pause, he pointed to a particular equation (aficionados may like to know that it was a version of the now-famous ‘Price Equation’) and said: ‘I really like that one.’

I think all his friends have their own stories to illustrate his shy and idiosyncratic charm, and these will doubtless grow into legends over time. Here’s one that I have vouched for as I was the witness myself. He appeared for lunch in New College one day, wearing a large paperclip attached to his glasses. This seemed eccentric, even for Bill, so I asked him: ‘Bill, why are you wearing a paperclip on your glasses?” He looked solemnly at me. ‘Do you really want to know’’, he said in his most mournful tone, though I could see his mouth twitching with the effort of suppressing a smile. ‘Yes,’ I said enthusiastically, ‘I really really want to know.’ ‘Well,’ he said, ‘I find that my glasses sit heavily on my nose when I am reading. So I use the clip to fasten them to a lock of my hair which takes some of the weight.’ Then as I laughed, he laughed too, and I can still see that wonderful smile as his face lit up with laughing at himself.

…

Any other scientist of his distinction would expect to be offered a first class air fare and a generous honorarium before agreeing to go and give a lecture abroad. Bill was invited to a conference in Russia. Characteristically he forgot to notice that they weren’t offering any air fare at all, let alone an honorarium, and he ended up not only paying for his own ticket but obliged to bribe his own way out of the country. Worse, his taxi didn’t have enough petrol in its tank to get him to Moscow Airport, so Bill had to help the taxi driver as he siphoned petrol out of his cousin’s car. As for the conference itself, it turned out when Bill got there that there was no venue for it. Instead, the delegates went for walks in the woods. From time to time, they would reach a clearing and would stop for somebody to present a lecture. Then they’d move on and look for another clearing. Bill wondered if this was an automatic precaution to avoid bugging by the KGB. He had brought slides for his lecture, so they had to go for a night-time ramble, lugging a projector along. They eventually found an old barn and projected his slides on its whitewashed wall. Somehow I cannot imagine any other Crafoord Prize winner getting himself into this situation.

His absentmindedness was legendary, but was completely unaffected. As Olivia Judson wrote in The Economist, his duties at Oxford required him to give only one undergraduate lecture a year, and he usually forgot to give that. Martin Birch reports that he met Bill one day in the Department of Zoology, and apologized for forgetting to go to Bill’s research seminar the day before. “That’s all right’, said Bill. ‘As a matter of fact, I forgot it myself.’

I made it a habit, whenever there was a good seminar or research lecture on in the Department, to go to Bill’s room five minutes before it started, to tell him about it and encourage him to go. He would look up courteously from whatever he was absorbed in, listen to what I had to say, then rise enthusiastically and accompany me to the seminar. It was no use reminding him more than five minutes ahead of time, or sending him written memos. He would simply become reabsorbed in whatever was his current obsession, and forget everything else.

Now let’s turn to Hamilton’s preface. I think it provides just a wonderful case study in melancholy — of what intellectual life is like for a certain type of neurodivergent heterodox thinker working in taboo subjects. Hamilton, somewhat unusually for this type of scientist, wrote beautiful prose, and, as Dawkins put it, “carried much poetry in his head”. The selection reproducing here is quite long, and is presented just for amusement and not with an eye towards arguing any specific point. I will occasionally interrupt to add some commentary.

Preface to Narrow Roads of Gene Land Volume 2 (1999)

It seems to me that in the concept of Culture we should recognize a spirit akin to some clever and determined braggart; if true, then be cautious about what he says. Of course it’s not that this guy is actually a nobody or unimportant, rather that always he likes to pretend himself more powerful than he is. And part of his bragging is to diminish, where he can, status of his senior colleagues—that is, he diminishes ‘instinct’ or ‘nature’ as variously called.

I see it as Culture’s very nature to put out a continual propaganda for its predominance. It is known now how autists, for all that they cannot do in the way of forging human relationships, detect better out of confusing minimal sketches on paper the true, physical 3-D objects an artist worked from, than do ordinary un-handicapped socialites; in short, autists often develop as gifted visualizers. Like these, then, and like also those colour-blind, who, as it is likewise now known, crack visual crypses and camouflage of some kinds all the better for having their ‘handicap’, so may some kinds of autists, unaffected by all the propaganda they have failed to hear, see further into the true shapes that underlie social phenomena.

My first story. When I was a junior lecturer at Imperial College in London in the mid-1960s, still trying to understand the evolution of altruism and sex ratio, the Royal Society of London set up a Population Study Group to ‘become thoroughly well informed about the scientific aspects of important population problems’ and to report to the society these causes and implications. In Britain, products of the ‘baby boom’ that had happened just after the Second World War were approaching adulthood and their numbers were demanding government attention; in most parts of the world a population explosion based on the spread of Western scientific technology was in full swing. To alleviate anxiety as we listened to predictions made of human doublings in extraordinarily short periods, there was much talk of the ‘demographic transition’, that pattern of preference and practice making for small families, begun in Western Europe and thence spreading eastwards and also to the whole of North America—in short, spreading in a mere 50 years through all of what were then the world’s most affluent nations. At the time, however, and in most areas of the world, the future arrival of such a transition had to be taken on faith. In spite of encouraging far-off examples occurring in, for example, post-war Japan, it was not clear then (and I would say still isn’t in, for example, Africa) that all the world was going to follow the ‘Western’ pattern of abundant use of birth control that made the transition possible.

It is a part of the constitutional intention of the Royal Society to be ready to give advice to the British government on anything within the scientific ambit. At the same time plain curiosity makes members of the society always keen to advise themselves. So interested fellows, perhaps in this case spear-headed by their president (of whom more in a moment), had brought together a study group of experts and arranged for them to have space and to meet once a month in the society’s rooms. The RS rooms were then in Burlington House, that ornate building in Piccadilly, London, which houses also the Linnean and Geological societies and, as the best known to the public, the Royal Academy (visual arts). The group was to discuss what was happening to population, what was likely to happen, and, although any pronouncement on desirable policy was very far from its main objective, the group was to try to tease out causative threads that might be useful. Demographers, economists, public health people, and reproductive physiologists were among those invited. The chairman of the group was Lord Florey, co-Nobel laureate (with Ernst Chain) for developing penicillin. In the same year as the group was started he was made a British life peer, and simultaneously was the President of the Royal Society itself. Sir Alan Parkes, a reproductive physiologist (I had attended a few lectures from him while I was an undergraduate at Cambridge), and Dr G. A. Harrison, human geneticist, were the group’s secretaries and the main organizers. My supervisor at the London School of Economics (LSE), John Hajnal, a demographer whose work was very much within the field to be covered (he had published, for example, a wide-ranging study of the demographic transition as it had occurred in Eastern Europe—indeed, I think the very idea of the demographic transition stemmed partly from this pioneer paper), was a starting member of the group.

After a few meetings John suggested my name as one who could profitably attend. Whether he meant profitably from the group’s point of view or from mine I have never been quite sure. I went in the spirit that being invited was an honour and that it was indeed a subject in which I was interested, and one on which I had been accumulating facts and ideas relating to ‘fitness’ and reproductive altruism; and, finally, I went thinking that possibly something out of what I was thinking for myself or collecting in libraries might be useful to them. I expected from the first to be learning far more than contributing; but most who attended also spoke at least in the discussion time and I didn’t suppose that I was expected to be just listener.

I remember vividly the dim-level theatre in Burlington House with its dark upholstered chairs and the dais at the front uplifting a rather grand and heavily leathered throne for the President (a reddish colour comes to my mind); oddly enough I don’t remember very much of who the speakers were or what they talked about. Nor do I remember much of the subsequent discussions nor any drastic new insight coming. But was it there, perhaps, that I learned from one speaker that the humble potato brought from the Andean civilizations of America soon after Columbus might count as the prime cause of the ‘spawning’ populations in Western Europe, and particularly in Britain, during the industrial revolution—this introduced new crop doing more for the mass well-being that sooner or later yields babies than did the revolution itself, and more also than the advent of hygiene and scientific medicine that shortly followed?

It may have been so, and in that case there was at least one important idea. But what I certainly learned fastest from listening, was that population growth and all thoughts associated with it were obviously subjects of intense and acrimonious differences of opinion amongst everyone, whether experts or not (the ‘nots’ I knew about already from ordinary conversations, it was the ‘experts’ that were a surprise to me). Some present thought the worldwide situation very serious; others equally definitely thought it was not; some thought growth was always good for economies and for standards of living—all peoples deserved their growth spells and the ‘West’ couldn’t tell others not to do that which, with great profit, it had done for itself; others argued passionately that this was shortsighted and the cultures would regret their present explosions and should be encouraged to slow down; some believed modern birth control was a heaven-sent answer, others seemed vaguely opposed to it; as to its methods, some appeared to believe in the one range while intensely disapproving others; and so on.

As I listened in silence I drew one general conclusion: for us to be so passionate about a topic we must be close indeed here to that centre of my actual and hoped-for expertise—biological fitness. It must be because of such a proximity to the deepest evolved roots of our psyche that no one seemed able to address the subjects of reproduction and population in a dispassionate way (I could tell from my own feelings as I listened to some of the points that ready-made passions and lack of objectivity were present in myself). Well, wasn’t this all just as I should expect; wasn’t it indeed a topic in which I should expect our deepest urges to be concealed almost from our very selves only in order that, in our everyday commerce with others, we would avoid being forced to expose ultimate objectives in ‘everyday’ discussion—not expose, that is, personal, family, class, or racial ultimate biases, rather to put on view an agreeable and softened version, a general hypocrisy, something to the effect that it doesn’t matter who reproduces, that we treat all people and groups with equal favour? That we all hold, whatever our specific denomination, a pan-religious view to the effect that ‘all men are brothers’ when actually we know very well, deep down, it isn’t true?

After sitting through several meetings in silence, I began to think it was possibly unsocial of me to remain so completely non-contributory; I felt almost as if I was a spy. Surely I ought to be able to say at least something out of my studies—all those long hours in the LSE library, my laborious extraction and differencing of figures from the heavy United Nations paperbacks on population growth, even if it had to be merely some off-the-cuff points about hiddenness of motive and potential hypocrisy such as I have just written. Those points, however, were difficult to put over and they weren't yet very clear in my own mind: for example, I foresaw justifiably irate rejoinders from psychologists challenging this or that about my naive version of the subconscious (a basically Freudian scenario of the subconscious was still very ascendant in those days; the more rational and data supported evolutionary version still waited to begin with Bob Trivers, and his first paper was some 6 or so years in the future). Therefore I took my cue from something else.

At the beginning of one of the sessions there was a discussion about the general course of the group’s programme for the future— who we should invite to talk and what about. I suggested it might be useful for us to discuss the psychology of population situations and to give special attention to those where closely placed or intermixed distinct groups had strikingly different rates of increase. In particular, it might be useful to consider what this might do to competitive birth rates and aggressive instincts connected with population perceptions—in fact, also with the inception of wars. There was silence as I stopped. I’d wanted to explain my thought as far as I could in words that didn’t bring in my pet and as yet little accepted views about the importance of genetical kinship for human altruism and aggression. It had seemed to me that my case for the interest of this topic could be made for present purposes without that and based on known historical instances by themselves.

The silence that came surprised and unsettled me, so I added something about every one having pride in his or her family and, perhaps not wanting to see descendants lost in a sea of strangers; while, in anything like a democracy, people would be not liking to imagine their own preferences and way of life being over-ridden by decisions deriving from ways of life either—for example, not caring about the countryside, urbanizing as far as possible, and so on (‘and so ons’, together with a good sprinkling of ‘ums’ and ‘ers’, which I omit, were inevitable in my speech of those days, as I remember it). But I think it wasn’t any of these traits that caused the silence that again followed. Then someone said something like: ‘This suggestion goes a bit beyond our brief, doesn’t it” What, couldn’t they see that these ideas did affect population issues?

In an effort to be more explicit and to be taken more seriously, I then exposed some corner of my actual work, saying something about how we were all expected, as a result of population genetical processes—natural selection in fact—to have psychological biases that wouldn’t necessarily be easily visible on the surface but whose reality would come to the fore in situations where these rapid changes in a population’s composition were imminent. There was a matter of within- and between-group variances involved here, this applying to the very genes that made us. It wasn’t necessary to such ideas, I added, that shortages of land or whatever would be apparent right when divisive psychology took effect; it would be in this nature of the group psychology to anticipate what might be about to happen. (Somewhere around this point Lord Florey came to his feet.) If we really wanted to understand why population is a difficult issue to discuss and to do anything about it in the world, I continued (rather desperately and speaking into a still intense silence), it is very essential that we understand the evolutionary forces that have moulded reproductive and territorial psychology in humans—the features must be old, of course, started doubtless mainly in our Old Stone Age past. If we wanted to recommend policies to affect population trends in any direction today, we perhaps needed to discuss first the underlying motivations that all people had to possess—that must be there from the very fact that they themselves came from successful parentage and successful families of the past...

I’m sure I wasn’t quite as coherent in this as I make myself appear now, but in essence that was my suggestion of a new topic. My description had come out a bit longer than I had intended because as I started I sensed the opposition the idea seemed to generate. I have put in the word ‘policies’ above because without it Lord Florey’s response to me would be even more incomprehensible than it was: I don’t recall that I used it, don’t see why I should, but I might have. I cannot reproduce Florey’s exact words as he interrupted me but remember something like this: ‘I really must interject here and make a clarification. My companions in the Royal Society decided it would be worthwhile to set up this group so that we could seriously inform ourselves about all factors bearing on human population, a topic which seemed to be becoming a vexed one in the mind of the public. But there have to be limits, a division between facts and fantasies. If our young friend here thinks that I, as their representative, am able to persuade them to march with banners in the streets on any particular issue concerning population, he is quite mistaken. I suggest (he turned to the rest) we discard this suggestion and move on to something more serious.’

Of course, I lapsed back into my habitual silence, but I felt extremely hurt at such a response to my first attempt to say anything and I wondered yet again why anyone had thought to invite me. Florey was very obviously agitated and angry and I couldn’t see why: why didn’t this group even discuss what they thought I had said? What had I said? I sensed from looks a rather similar haughty annoyance in several others in the audience. Yet where had I even hinted anything to suggest banners and marching? It was true, of course, that racism was indeed an underlying theme in what I had mentioned and racists probably did sometimes march with banners; but what had that to do with the investigative spirit of my suggestion? Might it be actually I had said then and there—had he perhaps read my paper about kin selection, imagined racism somehow in that, and formed his comment accordingly? I felt, actually, that my study had indeed enabled me to understand racism better than most, and, well, if that was implied, why not discuss it—didn’t a population study group need to understand so widespread a phenomenon? Wasn’t it true that racism had had indeed a very big effect on population composition in Europe itself even within the past 25 years? As it was, Florey was not done with me even in silence. In summing up the decisions of that session at its end he came back again to the talk of banners and marching and his colleagues in the society being not of that type, not subject to fanciful exhortations, and how he would wish this to be kept in mind during all future meetings.

After Florey had said this the second time and as the group began to disperse I wondered whether I should go to him at once to try to find out what he imagined I had said. I waited in the hall as it emptied but saw him immediately enter conversation with two or so others and they were still talking as they passed me on their way out. As he passed me I caught a glance that might have been somewhere between curiosity and guilt, as if he knew he had been unfair; but with it there still was a stony and lofty air that promised no further discussion—also I thought later he had the look of a man who was tired. I had seen the same expression many times in the past on my professor’s, Lionel Penrose’s, face many times when he passed me in silence in the corridors of the Galton Laboratory, and my returned expression probably wasn’t too dissimilar, perhaps betraying my thought that I, too, can do without his discussion, but won’t go away. But in the case of the Royal Society Population Study Group I did soon go away. I attended for perhaps three more meetings; then I decided I had absorbed enough of all the leather smell and panelling and the (to me) superficial and quarrelsome opinions: I made an extra shadow in the dark seats no more. Later I thought how my attendance had been like my presence in my school chapel: there, too, it was awesome and dim and had become boring by repetition, and there was a silent boy. In that case, having been always totally unable to sing any sort of correct note or harmony, I would, when pressed by a prefect, open and shut my mouth silently like a fish, mouthing hymns as required, but mostly thumbing through my book and trying to find for my own inward recitation the few hymns that were passable as poetry (mighty few). In Burlington House it was as if a prefect had been watching me once again: but well, wasn’t I a step further? At least this one hadn’t ordered me to mouth out the beliefs I didn’t hold.

That perhaps two-minute speech suggesting a topic was my only attempt to contribute anything to the Population Study Group meetings. It was the only time I opened my mouth apart from occasional hushed comments to John Hajnal, who sometimes sat beside me. I think the group itself didn’t last very much longer. Shortly I learned that Florey himself was seriously ill with cancer. I felt more understanding towards him then and guessed why he had seemed tired. In all of his handling of the meetings there had been something of the same disappointing impatience as with me, although it was less intense. It seemed to me the same peevish spirit as I had noticed in Sir Ronald Fisher the last (and only second) time I had seen him at his Storey’s Way edition of the Genetics Department of Cambridge; he, too, had been due to die of cancer in about two years. Fisher had been talking to his assembled tea-time group about the evidence for the link between smoking and cancer—Austin Bradford Hill and Richard Doll’s results, all deep and rational but slightly high-pitched in tone. But not all elderly, sick, and eminent men seem to have to be like that: I didn’t see the same in J. B.S. Haldane, for example, who was also pale with cancer and dying when I had seen him lecture in University College in about 1962; perhaps I did see a trace in Allan Wilson in Kyoto in 1989, as will come in Chapter18. Florey died in 1968.

The Royal Society’s next president, Lord Blackett, oversaw what Florey had begun—the society’s move to its present, more magnificent and less shared building in Carlton Terrace, the big cream-coloured block near the Duke of York’s statue and overlooking St James’s Park. I was to begin a vastly more satisfying and respected relation with the Royal Society; in fact, in that very year 1968 when they first financed me to go to Brazil to study wasps and at the same time selected me to join the big Royal Society/Royal Geographical Society expedition in Mato Grosso; 10 years later still I myself became one of those august, never marching (and, I hope, seldom un-listening) Fellows of the society.

My second story. In the autumn of 1998, perhaps because of having now several international prizes behind me, I found myself invited to join another study group and this time specifically to address it. It was to be a brief meeting in the Vatican; again there was some kind of ‘society’ behind the meeting that wanted (it said) to become more informed by science. The subject was definitely not population although that topic was far from banned: we were being encouraged to cover the whole of the philosophical ambit of science. The Pontifical Academy of Sciences of the Vatican had called a meeting of scientists, historians, and philosophers to discuss ‘Nature’: what did this ‘Nature’, human or otherwise, mean and how had the idea of it changed down the ages? How would Nature be seen in the early years of the next millennium? Quantum physics, cosmology, genetics, evolution, humanity, and culture were all to be included.

I thought it an excellent idea. Were the conference proceedings to be published? This was an important point for me from the start. It wasn’t clear. The preliminary guiding documents that I and some dozen or so outsider invitees received indicated that written versions for our lectures were indeed part of the deal—the free trip, etc.—but no promise of publication seemed to be made (or threat as I more usually see it, because that prospect with its thousand eyes inspecting for all time involves me in vastly more work). I was listed in the draft programme to talk about developmental biology as affecting this topic of the nature of Nature. It wasn’t my field at all and there had been some mistake. In my reply to the inviting letter I therefore pointed out my complete inexpertise on development and in general I was a bit discouraging about being able to find the time even if given a task in my real field, if a serious written contribution was expected. Father Pittau, SJ, the then organizer, wrote that they would like to have a talk from me anyway; I could suggest my own title in the general area of evolution.

I then asked myself what was the real objective of the Pontifical Academy (which to my mind, for all the claim that it stood completely apart from any ecclesiastical control, must mean the Vatican and all its hierarchy) in holding the conference. What did they expect from the face-to-face discussion? If Roman Catholics really wished to inform themselves on the state of any branch of science, it was all out there in textbooks and journals anyway; indeed, in my field of evolution I knew they already had excellent scientists within the Pontifical Academy (Luca Cavalli-Sforza and Peter Raven were examples). Why couldn’t they simply consult them—why call in outsiders like me? Was it just that they wanted the loan of names of scientists like me that they could attach to a conference they would announce to have been held within the Vatican, and use this to reinforce amongst their own as well as outside intellectuals an impression that the Pontifical Academy, and Catholic thinking generally, was seriously in touch with science and was deemed by the outsiders to be a worthwhile scientific institution?

If that was all in the present case, I was not keen to lend. At the same time, I was aware that the Pope had seemed recently to be trying to achieve some rapprochement of his religion with science. After 300 years (!) of silence he had at last admitted to a mistake made by the Catholic Church in bringing Galileo to trial and forcing him to recant over his support for Copernicus; he had likewise regretted the burning of Bruno; not least in his last encyclical he had explicitly admitted that evolution, at least within limitations to the non-human(and especially non-mental world), certainly had occurred by natural selection just as Darwin had said. There seemed, in short, to be a genuine spirit and apology, rectification and updating abroad in the Catholic Church—a clearing of old rubbish, one may say, from its decks before its grand ship went steaming across its own (in a sense) self-made line into the new millennium.

If this second spirit, or something like it, was the real one, I thought, might the Catholic Church be receptive to further evidence that various of their present doctrines were, in fact, travesties of any ‘accords with Nature’; indeed, were such frontal assaults upon the principles of evolution and ecology, including as these affected humanity, that in the long run (at least here on earth) they could not possibly persist? And could they be persuaded to see that, pending the collapse that must come, these doctrines were making the world into a much worse and less happy place for humanity to inhabit? If such open mindedness was the spirit of the day I would be glad to help. Any change in Roman Catholic doctrines that are contributing to overpopulation, for example, would be a big step and I would much like to contribute to that.

There was also the issue of human health. I knew well that it was not deep in the nature of any branch of Christian religion (or perhaps of any religion whatever) to care much about this. Because according to many religions all our physical troubles are put directly or indirectly in our way by an omnipotent Being in order to test us; and because faith and miracles supposedly can cure them; and because, on the more pragmatic plane, beliefs of such a kind held by the afflicted faithful keep their minds and donations oriented towards churches, it is easy to see that theological and pragmatic viewpoints accord quite neatly: in short, there is no good reason for religions and their ministrants to want to see better average health. The extra interest the chronically sick have in religion is evident everywhere but is especially prominent at particular centres such as Lourdes and Loreto. But not even Catholicism could want all people to be so physically incompetent that civilization, and, with it, all the splendour and effectiveness of their earthly world would have to break down. It wasn’t just the ballrooms that would fall silent: the very engine rooms themselves of the grand liner Catholicism, on which decks they were effecting minor tidyings for a coming ‘Crossing of the Line’, would eventually go silent, too, and the ship split apart. To my mind this actually happening is not such a remote possibility.

Thinking in this way about what I could say about average human health as its basis was changing under present civilized and sentimental policies, with these commonly abetted by having their sentiment recast as religious dogma, it occurred to me that here was a useful thing I could possibly do for the meeting and this perhaps could be without too much time committed. One of the ‘introductions’ I had already drafted for this book seemed almost as if ready drafted for a paper on this topic. I could rewrite and re-orient it a bit to suit the symposium and, with an effort, have ready a publishable manuscript in good time. I was thinking of the introduction that I had already completed as a first draft for Chapter 12 of this volume…

Chapter 12 refers to “The Great Planetary Hospital”, which I wrote about here.

…I therefore replied to Father Pittau that I could come if he would accept a talk from me on the following theme: ‘Changing and evolving nature: health and human paths in the next millennium’. Father Pittau replied that the title was fine and he was pleased that I had accepted. As often happens my first choice of title soon seemed to me clumsy and by the time of the meeting I had changed it to ‘Changing and evolving nature: the human and the rest’. But the idea was the same.

I intended to cover on the one hand how drastically we were indeed, in the short term, changing our external and environmental ‘Nature’ by the combination of our technology and our overpopulation and on the other how, in the long term, we were changing (and in this case micro-evolving for the worse) our own internal Nature’—that is, our own genome. To a substantial extent the latter trend was coming through our recent and unnatural ethic that every conceptus, no matter how mutated, was deserving of every technical effort we knew to make it survive. I would try to convince the conference that these two trends in the present situation of sentiment tied to ever-advancing technology had to be on a collision course from which our only escape, other than the collapse of civilization and thus collapse of the infrastructure to continue the policy, would be the advent of truly superorganismic, superhuman integration. But this, if it came, would also bring in the end attitudes towards frail human bodies that neither the Catholic Church nor irreligious people of the present day would at all like to contemplate, an opposite to that valuation of individual life intrinsic to the utopia inspiring our initial efforts. Like Alice in the looking-glass garden we did not yet realize that as we headed childlike for where we wanted to be, we actually found ourselves carried the opposite way.

You will find this argument in more detail in the introduction to Chapter 12. The manuscript I submitted to the Pontifical Academy organizers can be imagined from this introduction fairly accurately by just assuming absent from the essay all the parts that refer to Gustavus Adolphus College and the symposium held there (that was where the paper the introduction is introducing was delivered—sorry, if this is all a bit complicated) and also by imagining stripped away all the parts referring directly to the ‘introduced’ paper itself. The whole ,it has to be admitted, has ended a rather rambling and long essay, and I also admit that the version that went to the Vatican was similar; however, when you have glanced through it I ask readers to judge for themselves whether the events that followed with my contribution at the Vatican symposium, which I now describe, were justified.

The setting for the symposium in October 1998 was delightful, even awesome—at once intimate and grand. The Pontifical Academy had long ago been given as its headquarters a villa built in the mid-sixteenth century for the accommodation for Pope Pius IV in the gardens behind St Peter’s cathedral. These gardens covered a section of hillside that sloped down towards the foundations of the cathedral. They were lovely in themselves and for the faithful visiting St Peter’s (visitors who, unlike us, would only exceptionally be allowed to wander there but who might from various points distantly see them) their palms and cycads, their lawns, and their wonderfully constructed rockeries and fountains might seem like a foretaste of paradise itself. Over the gardens and our building on one side loomed the bulk of the cathedral, the world’s largest church, topped by Michelangelo’s soaring and perfect dome; on a second side the gardens were shut in from a view towards the city of Rome by long ranks of the windows of another almost equally massive building, the Vatican Museum. The past papal villa, the conference building, was a museum piece itself, a treasure (especially within) of antique architecture and decoration. In its central hall where we talked (and where Pope Pius IV perhaps had given audiences) now tiers of high-backed wooden seating arrayed three of the sides while provision for a screen was set against the fourth. Every seat was provided with a microphone and when in session all the seats of the room were filled. The conference was maximally attended. Perhaps there were about a hundred of us in all and of those pre- sent perhaps one quarter were showing in their clothing at least some token of ecclesiastical calling, but my impression from some types of questions and comments was that a somewhat higher proportion might have had some connection with theology.

The day after my manuscript had been handed in, it turned out that the programme for the meeting had changed. I found myself scheduled to give my talk as the first in the morning of the third day instead of on the second. I arrived that following day at the appointed 9 o’clock ready to speak but found a blackboard announcing still further rescheduling; among the new changes my talk was now put back to be second last of the morning, of what was to be the last half day of the meeting. I began to feel a bit worried and suspicious that I might have wasted my long efforts with talk and manuscript.

Next day at 9 o’clock the morning and last session was launched; and, rather as I anticipated, the earlier talks ran on in quite leisurely fashion. First, unfinished matters had to be wrapped up from the previous day. The conference had gained time from the fact that Stephen Jay Gould, scheduled in the programme as we received it on arrival, had not come. But other things running late had already eaten up his time. Now this morning, however, the organizers tried hard to fill in for Gould. Every speech was supposed to be ‘commented’ upon in a counter speech given by an appointee from the Pontifical Academy who had been set to study each submitted paper. Although Gould had not spoken the previous day, and no one knew what he would have said, the counter speech by his commentator seemed still to be necessary. This speech was given and after it an elderly philosopher in the audience (who, in another ex tempore address on a previous day had informed us he had published 49 books) gave little speech of his own in the question time, stating his view that, as regards this question of evolution, all ‘ultra-Darwinism’ was now proven to be nonsense. As a valid contrast to ‘ultra-Darwinism’, he enlarged on the philosophic importance of the verb ‘to be’—‘essere’ as it is in the Italian, he explained. When he had finished, the chairman of the morning session then added some 15 minutes of his own comments on evolution theory. Seemingly this was a further fill-in for Gould and he included mention with no detail of recent theory that he believed in (and I imagine Gould does not) ‘evolution genes’—that is genes differing in function from all other classes of genes and whose specific purpose was to speed up evolution progress when such speeding was needed. At the end of this, the time for me had arrived, but just before I took the floor the chairman warned me that I now had only 20 minutes for my talk and that this would have to include the questions (the original allocation had been 45 minutes): we were desperately tight for time, he told me, and I must remember there was another speaker to come after me and before lunch and thus before the end of the presentations.

It hardly needs saying that under continual contraction of my time relative to what I had prepared for, my presentation was hurried and truncated. There was time for just one question and two comments; both the latter were hostile and dismissive of my points and there was virtually no time for me to respond to them. My appointed commentator then took the floor and told us very amiably how he so disagreed with my paper he could not try to address it; instead he would talk about historical issues in the history of science and art that had interested him; these had been raised in another talk.

We descended through the ornate passages and stairs to lunch, which, as usual, was very good. After lunch those at the meeting who were members of the Pontifical Academy entered a closed session on academy affairs and the rest of us drifted away. I left the meeting with a sensation of how almost nothing had changed in the 40 years since I had been similarly ‘put down’ by the President of the Royal Society when I tried to suggest something at the Population Study Group meeting as I described above. Some subjects are simply taboo in our society and they have remained so in both London and Rome for at least 50 years. In the London case I imagine I had been invited to attend the meetings because John Hajnal had billed me to the group as a ‘serious young man’; now, known as a Crafoord and a Kyoto Laureate, I was often sought after for conferences like the present one—but, when the conference topic was like that of the present one, it seemed I was still only sought by people who didn’t know me, and who had not been warned! Just as in London, when it became apparent what sorts of things I had to say, the organizers and chairmen, who tend to be, even among scientists, the more political types, would avoid, almost at any cost or rudeness, allowing me to be heard. Will the reader who has reached to this paragraph be different from this? I must wait to know.

Meanwhile, I believe, the warnings I try to give at those kinds of meetings are one by one coming true. The streets of Belfast in 1966 seemed a long way from the dignity of Burlington House but at the same time perhaps too close and too much of a political issue, and if I remember there was actually not much fuss in Belfast in 1966. Likewise the rounded and over-cultivated, lived-on hills in the then infant state of Rwanda were also far away and no one was worrying—and nor were they about the hills of Kosovo. Yet, now, how can it be that people can still shut their eyes to those so obvious causes of group strife that I had said we should discuss? Even in the past few years a book has been written (E. Sober and D. S. Wilson, Unto Others: The Evolution of Altruism, as cited in the introduction to Chapter 4, note 18), claiming for group selection a power almost equal to individual selection; all of the rosy side of this picture—the group amity, the advantage within the group of honest communication, and so on—is fully detailed in the book; the other side of group selection, exactly the group strife that in 1966 I was noting and saying we should consider (in 1971 I called this the ‘other’ or ‘warfare’ picture, on Achilles’ shield—see the frontispiece and p. 217 in Chapter 6, Volume 1 of Narrow Roads of Gene Land) is given the briefest of attention and is treated as if it was largely avoidable through acculturation of disadvantaged groups into the positively selected and dominating ones.

As I write and as ‘ethnic cleansing’ continues in the supposedly unified nation that was Yugoslavia, I ask myself, on lines of such acculturation being a conceivable answer, is it possible for a young male Kosovar to avoid being ‘cleansed’ out of his life or, if luckier, simply out of his country, by his saying he wishes to convert to ‘being a Serb’? Can an Arab in de facto Israel keep his time-honoured land on the West Bank by saying he wants to be a Jew—can he even retain it if he adds that he will scrupulously observe observances and turn up each week at the synagogue? Back again in Yugoslavia, if a woman Kosovar states that she accepts racial justice in her Serbian rapist’s act, acknowledging his great genetic superiority to her husband, and that she will try henceforth to rear a good ‘Serb’ out of the man’s (or men’s) issue, is she then spared and supported?

To all this, the answer is obviously not. Far better would it be then, if the prevention of what is actually happening in these places had been started at a much more basic and philosophical level and even with scientific, dispassionate discussion in such places as Burlington House, and thus started out with evolutionary understanding of what we are. With or without believing in my particular line of theorizing, wouldn’t that have been better than sending out the present mix of bombs and aid teams to Yugoslavia? Wouldn’t it have been better for the United Nations, 40 years ago, to have at least been given the grounds to understand that all areas in the world where two races (or indeed any two forms of cultural identity) show strikingly different and above-replacement reproductive rates are likely soon to turn flash-points for war and genocide—and for the UN (or UNESCO) to have tried at least to warn the occupants of such regions where they are heading? I even see a role for the World Bank in the sorts of preventive inducements that could be applied: money should only be lent to the degree that receiving cultures show they are serious in reducing the inflammatory growth rates they currently support (or/and in reducing those rates likely to cause outward conflagration between their own culture and another). A simple pragmatic ground for such refusal of aid would be that there is no point to try to better a country economically by making it loans if all gains are soon to be burnt up very shortly in war and massacre. But there are also reasons that are much more ethical than this- perhaps it would be possible for all gypsies, for instance, to disappear suddenly and ‘cleanly’ from a country with little economic consequence; but that doesn’t make such a disappearance any less wicked and undesirable. Persuasion about foreseeable consequences, and misery to come, is surely the route of reason and it is this route that establishment interests seem still to attempt to deny to me.

I don’t mean that I could not have got around these setbacks, and, in the Vatican, I wasn’t hauled off to be shown, as gentle persuasions for me to stop rocking the boat of virtue, the instruments of torture in the cellars as may have been shown to Galileo and Bruno. There were just polite goodbyes. But what, for example, should I have done after that earlier parallel interaction with Britain’s most august scientist—laureate, lord, and PRS— in Burlington House? Should I indeed have dived back into geography, into history, back into the library at LSE, ferreting there still further through the UN tomes on population growth plus mining all the older books on historical demography—and, out of all this, proved my point in print, a matter of history, no theory involved? I am sure I could have done it. But really the point at the time seemed to me to be already too obvious to be very interesting. Besides this I was engaged in another rather similar but more intricate endeavour that was taking up all my time. I was trying to prove myself right against all those, including my former professor, Lionel Penrose, who had told me that there was no such thing as genetic altruism or genetic selfishness or aggression, and that, here again, I was on a wild-goose chase.

…

Now, what should I do to reply to the event in Rome? I suppose once more the most direct answer is to gather evidence documenting the abundance, the insidiousness, and the inevitability of human deleterious mutation and write a book about it, convince people that something we don’t like will indeed happen and we can either forestall it or not. But, again, the matter seems to me so obvious, so almost like offering a tedious re-explanation of the second law of thermodynamics, that I don’t want to waste my time: what I do here instead is simply to re-polish my Chapter 12 essay and write this preface to enable you to picture what I had meant and what happened.

I predict that in two generations the damage being done to the human genome by the ante- and postnatal life-saving efforts of modern medicine will be obvious to all and be a big talking point of science and politics. It has taken about one generation for the trend I spoke of in that former suggestion—the matter of the strife-promoting effects of differential and above-replacement birthrates—to reach the point of obviousness that it has now. Because even that species of obviousness is not yet translated much into journalism or everyday political consciousness, it seems we might have to wait another 40 years before the world has come to the point where I feel I stood in Burlington House in 1966. Meanwhile on this other issue it seems it is going to be about the same. In 40 years civilized countries will have become uncomfortably aware of, for example, the increasing load of the intrinsically unhealthy on health services, the increasing dominance of both sport and everyday health-demanding activities by nations that have enjoyed the worst records of the practice of scientific medicine. The burden imposed by heavily ‘mutationally challenged’ people on the less challenged and the able-bodied will already be more obvious. But probably in 40 years most will still be saying it doesn’t matter, we can cope, and that the answer to everything—now fixing up the germ-line—is just around the corner (another implied prediction here is that because of a growing need to have at least some such hope while continuing to take the technological health route, the present restriction on experimentation with human germ-line and/or stem cells and with few-cell embryos will have to be lifted very soon). Anyway, step forward by another 40 years and I believe the validity of the themes I was trying to raise in my Vatican lecture will be easily apparent to every thinking person: it will be seen that Homo sapiens, at least in the so-called ‘first world’, is indeed entering a phase of medical metastability.

Metastability—the possibility of non-self-limiting breakdown—will hold with respect to potential epidemic disease agents, to potential physical disruptions (sudden climate change, asteroid impact, and the like), and with respect to sheer physical inabilities in daily life. The servicing of an essentially machine- and electronics-based culture will be ever more liable to an escalating breakdown. After 80 years 1 predict people will have begun to think seriously about these points. By then, I admit, there will still be enough time to back out, although it will only be to an accompaniment of considerable suffering. One of the ways in which I think backing plus curbing of the hypocrisies of individualism will come about will be through a greater measure of family responsibility that political parties will see it as necessary to impose: as example, if a family wants to keep a particular vegetable baby alive, the family must pay for it. Similarly, if a church objects to the alternative—letting the baby die—extra taxes to pay for the baby’s special care will be required from specifically that church’s coffers, backing its beliefs. None will be demanded from another church that agrees the baby should die. In general along such lines, it will be a great step in the equitable running of modern society if a sincerity tax comes to be imposed on all propaganda—what you say you believe in you must show you believe in through hard cash and sacrifice; as example again, there should be no option but that your own child attends the idealistic comprehensive school you say you believe in.

But why not start to discuss and make decisions and try experiences now? Just as I believe Kosovars should be allowed to practise Islam in Kosovo, in the heart of Christian Europe, if they want to (including even practise the purdah and female circumcision if they want that) but not including any right of unlimited increase (or at least providing very strong disincentive, in contrast to the recent supposedly liberal and yet embittering spirit of toleration), so I believe that other self-defined yet quite different groups of idealists should also be allowed to practise a religion that includes parent-decided selective infanticide, provided this is done under good safeguards against cruelty. Through free choice in idealism this will become real, effective group selection on the cultural plane, hopefully no longer contaminated from its warlike predecessor out of biology.

…

Throughout these two volumes I try to express how strongly I don’t believe in the above laissez-faire and short-term view of our future—and to give reasons. To be more serious than about crying children (though I’m serious there, too, within its time frame—I think it’s a case where most of us have already learned through some bitter lessons, either in our own present generation or by natural or cultural selection in the past, what the limits are), let me say that for a start I think the disaster-acceptance course may lull us into not noticing many other truly deadly dangers for our species. Indeed I think we are already lulled. In the bliss of the always easiest, quickest benefits, we may be forgetting to look much to our distant future at all. Deep in responding to ever-increasing clamour to be ‘humane’, to concentrate on the individual and immediate (and increasing) human needs— issues of Viagra for the elderly, for example—we may miss noticing in time, say, the coming asteroid, then find too late we have already forgone the chance to deflect it. Thus we may come to our extinction even without the help of our own asteroidal-scale wars that are so likely if we let population increase continue un-reprimanded and uncontrolled as we do.

…

Sadly I think few will read even this far. But for those who do read to here, and perhaps further, what more needs to be said in overall introduction to the series of essays and papers that follow? I have said little yet about the volume’s main theme, the evolutionary reasons for sex, even though these reasons as I will explain them are very much in the background of the above issues and, as you will see in the introduction to Chapter 8, they even provide the best evolutionary argument against the racism that so often comes to underpin the conflicts I have just mentioned (see the introduction to Chapter 12). I think for the whole of the book | just have to plead sincerity. I didn’t go to the Population Study Group meetings wanting to make a fuss, instead wanting to learn and, if I could, to help. Likewise I didn’t go to the Vatican meeting wanting to make a fuss. Rather, again, it was that they had asked for a contribution to an important theme and I wanted to give it. | am aware that vast numbers of admirable and idealistic people, including some members of that true superspecies of Homo, the true human altruists, are enrolled in RC ranks. Usually I seem to see them among minor clergy; they are those out among the people and in most cases if too sincere seem not greatly liked by their own superiors—or at least not until after they are dead and their reputations perhaps begin to demand what the people think. I would like to help all such sincere workers to be a more effective force than they are, to help them to play less self-defeating parts in the supra-animal future that is indeed opening before us. Basically, because this course is going to be above biology even while it still must take its models from biology, I even admire Catholicism in the way I admire any other vital and unusual organism—like admiring a beetle for its mysterious but beautiful horns or a honeybee hive for its workforce. Especially in the mix that this lot have created I admire the attempted celibacy of the RC priests—though I concur with others that they have created for themselves a crisis about keeping in touch. It is in such a spirit of sincerity, accepted, as I hope, by both religious people and agnostics, that I would like the book to be read.

Commentary

I will close with assorted unstructured points.

I think it is a great shame that Hamilton gave so much credence to nonsense about overpopulation. “Neo-Malthusianism” was already nonsense when it was first formulated in the 1960s, and had been completely refuted by the time Hamilton wrote this preface in 1999. The Green Revolution demonstrated that technology advancement can drive immense leaps forward in agricultural yields, outpacing population growth. That Hamilton cleaved to this way of thinking this late irrespective of evidence illustrates a certain dogmatism in his epistemics that is sad to see.

I do very much enjoy Hamilton’s proposal that churches pay for abortions they stop, and I support this policy at least in principle. We should search for methods such as this to fix misaligned incentives in moral discourse. Though analysis ex post can reveal the hidden costs of ostensibly moral policies (see for example this paper which showed that American children’s car seat laws have removed 145,000 people from existence over 40 years, while only saving ~50 lives per year), it would be difficult ex ante to figure out who is responsible for what, and therefore who should be subject to corrective taxes. This difficulty is not caused by the laissez-faire attitudes towards systematic disaster that Hamilton draws attention to; rather it is the general principle which makes us systematically undervalue counterfactual benefits and harms.

Really good. Only a man that believes in God cycles at such enormous speeds...