Daniel Dennett's "Real Patterns"

Reductionist ontology for those who think a lot of big stuff is also real

Abram Demski recently observed that there has been an encouraging trend towards convergence across research agendas in AI alignment theory:

Over the decade I’ve spent working on AI safety, I’ve felt an overall trend of divergence; research partnerships starting out with a sense of a common project, then slowly drifting apart over time. It has been frequently said that AI safety is a pre-paradigmatic field. This (with, perhaps, other contributing factors) means researchers have to optimize for their own personal sense of progress, based on their own research taste. In my experience, the tails come apart; eventually, two researchers are going to have some deep disagreement in matters of taste, which sends them down different paths.

Until the spring of this year, that is.

…

Steve Petersen also seemed excited about paradigm convergence at ILIAD, expressing excitement about trying to bring together all the theories of abstraction (Sam’s “Condensation”, Daniel Dennett’s “Real Patterns”, John’s “Natural Abstractions”/”Natural Latents”1, and Steve’s own formalization of abstraction). (Hopefully I’m fairly representing Steve here.)

Accordingly, I thought it would be nice to write a short and slightly opinionated explainer of Dennett’s “Real Patterns” (1991) paper2. Dennett’s paper is a fun read and very persuasive, so I encourage you to read it if you have the time. I’m going to summarize it here a couple times over, increasing the complexity of explanation with each pass.

One Sentence Summary

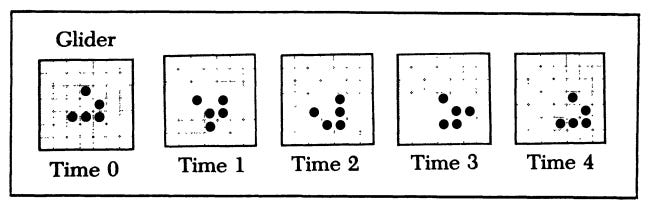

Causal reality ultimately only exists at the level of microphysics, but larger things (cells, chairs, etc.) and abstracta (centers of gravity, beliefs, Gosper guns, etc.) are “real” insofar as they are patterns that compress and predict data better than a lower-level description would; this is all that “real” means, and all we could want it to mean.

A More Detailed Summary

Metaphysicians are interested in pinning down the ontological status of many tricky phenomena, and many want a clear, binary answer about whether something ultimately exists or not. Most of us are happy to say that electrons exist simpliciter, as they are useful in physics, are things, and are part of the causal order of the world. But what about chairs, beliefs, vector fields, and lines of latitude? Consider the case of the center of gravity. Dennett quotes one philosopher who denies that centers of gravity exist strictly speaking, but are merely good approximations:

It is false, for example, that the gravitational attraction between the Earth and the Moon involves two point masses; but it is a good enough first approximation for many calculations.

Dennett quotes another philosopher who affirms that centers of gravity exist, but makes clear that you need to be extra precise about what part of the concept you’re claiming is real:

I am a realist about centers of gravity… The earth obviously exerts a gravitational attraction on all parts of the moon — not just its center of gravity. The resultant force, a vector sum, acts through a point, but this is something quite different. One should be very clear about what centers of gravity are before deciding whether to be literal about them, before deciding whether or not to be a center-of-gravity realist…

In both cases, the ontological status of “centers of gravity” (in the sense that we would use this concept in ordinary speech) is called into question because it can be largely or completely decomposed down into a more fundamental picture.

We could also choose to join pragmatists like Rorty, and say there is no matter of fact about what is real and what is not, and say that we can only really say is that “centers of gravity” are useful in some discourses and not useful in others. We’ll discuss this position a bit more later.

Dennett thinks that we do not need to make a binary choice between reality and non-reality, and that we can supply a precise, information-theoretic account of what it means to be “real”.3 This account centers on the notion of a pattern.

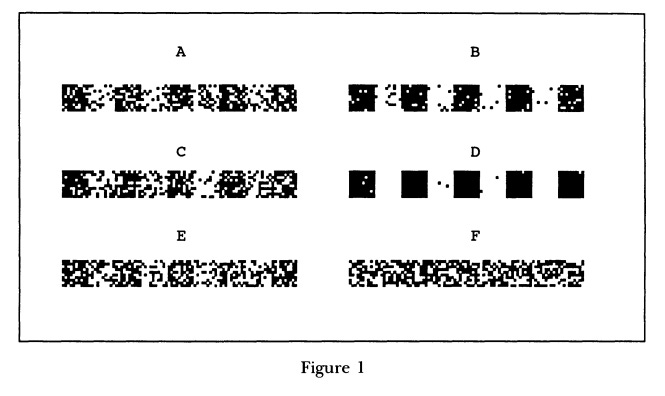

Here, Dennett wrote a program to generate these 6 “bar codes” each with a certain amount of noise added (A: 25%, B: 10%, C: 25%, D: 1%, E: 33%, F: 50%). We can see that there are discernable patterns here, but how do we characterize this fact precisely? We can use information theory:

Fortunately, there is a standard way of making these intuitions about the discernibility-in-principle of patterns precise. Consider the task of transmitting information about one of the frames from one place to another. How many bits of information will it take to transmit each frame? The least efficient method is simply to send the “bit map,” which identifies each dot seriatim (”dot one is black, dot two is white, dot three is white, …”). For a black-and-white frame of 900 dots (or pixels, as they are called), the transmission requires 900 bits. Sending the bit map is in effect verbatim quotation, accurate but inefficient. Its most important virtue is that it is equally capable of transmitting any pattern or any particular instance of utter patternlessness.

Gregory Chaitin’s valuable definition of mathematical randomness invokes this idea. A series (of dots or numbers or whatever) is random if and only if the information required to describe (transmit) the series accurately is incompressible: nothing shorter than the verbatim bit map will preserve the series. Then a series is not random — has a pattern — if and only if there is some more efficient way of describing it. Frame D, for instance, can be described as “ten rows of ninety: ten black followed by ten white, etc., with the following exceptions: dots 57, 88, …” This expression, suitably encoded, is much shorter than 900 bits long. The comparable expressions for the other frames will be proportionally longer, since they will have to mention, verbatim, more exceptions, and the degeneracy of the “pattern” in F is revealed by the fact that its description in this system will be no improvement over the bit map-in fact, it will tend on average to be trivially longer, since it takes some bits to describe the pattern that is then obliterated by all the exceptions.

…

A pattern exists in some data — is real — if there is a description of the data that is more efficient than the bit map, whether or not anyone can concoct it.

In this way we can affirm the reality of other abstracta. We can characterize the degree of reality of centers of gravity by seeing how much information we can compress and how well we can predict relevant data. In this way, the patterns we deem most real will be those that best carve reality at the joints. It also allows us to remove failed models from our ontology (even if we have some other pragmatic or ideological motivation to use them). If they can’t compress and predict better than our lowest-level description, then they are exiled.

A Formal “Real Patterns” Model

I’m going to give a simple information-theoretic model of the real patterns concept.

Let D be a corpus of data, and M be a set of models such that each m∈ M has:

A description length L(m) in bits (i.e. how complex the model is)

A code length L(D | m) (i.e. how many bits we need to specify D in full, given that m is known)

The Minimum Description Length involves the choice of model m such that:

So for Dennett’s example of barcode F, m will be the model encoding the hypothesis “F is 5 black square areas and 4 white square areas alternating, with some exceptional pixels”; L(m) will be the length of bits of this description; L(D | m) is the length of the description of the location of the exceptional pixels.

A pattern is real if we see an improvement in description length:

We can define the reality of the pattern to be the difference:

If R(m) is nonnegative then m is real. If R(m) is negative, then we chuck m out of our ontology altogether.4

Let’s probe this test model with an example. Say that we need to transmit alternating bits:

Our baseline is just sending every bit:

Let our pattern model m encode the hypothesis “N alternating bits sequence starting with 0.” We need log bits to specify N, and some constant c bits to describe what an “alternating bit sequence” is:

We don’t need to send any additional data in this case, so:

Making it clear that for large N:

Showing that the pattern has high reality. The way this breaks down for small N seems correct to me: “…is an alternating sequence” does carve the sequence “10101010101010…” at the joints, and doesn’t carve “101” at the joints (as long as that is the only data we want to explain).

Last Thoughts

The toy model above is obviously very simplistic, but I think it shows that Dennett is saying something nontrivial and useful, and that the core “real patterns” thesis can be productively precisified in future. Various research programs in structural realism refine these ideas. It is possible that work such as Ladyman & Ross’s Ontic Structural Realism could be gainfully added to the theoretical apparatuses of AI alignment researchers.

Addendum: Details For Philosophy-Enjoyers

I want to unpack here some of the arguments Dennett makes against Fodor, Churchland, and Rorty. Skip this if you aren’t interested in historical debates in analytic philosophy.

We need first to recontextualize the “Real Patterns” paper back into the philosophy of mind. Dennett wants to defend his account of the ontological status of beliefs (i.e. that modeling other humans as having beliefs is a real pattern, and therefore beliefs are real), from alternative accounts that push against his on separate sides. Dennett thinks Fodor and Churchland have altogether too high expectations for progress in neuroscience. Fodor is a realist about beliefs because he “takes beliefs to be things in the head — just like cells and blood vessels and viruses”; he thinks neuroscience will soon make discoveries to this effect. On the other hand, Churchland is an anti-realist who thinks that folk psychological notions like beliefs will be soon rendered superfluous:

Let us finally consider Churchland’s eliminative materialism from this vantage point. As already pointed out, he is second to none in his appreciation of the power, to date, of the intentional stance as a strategy of prediction. Why does he think that it is nevertheless doomed to the trash heap? Because he anticipates that neuroscience will eventually-perhaps even soon-discover a pattern that is so clearly superior to the noisy pattern of folk psychology that everyone will readily abandon the former for the latter (except, perhaps, in the rough-and-tumble of daily life). This might happen, I suppose.

I believe Dennett was correct in pushing against these expectations.

Rorty’s pragmatic irrealism is close in some ways to Dennett’s position, but is underbaked and altogether too lenient:

What then is Rorty’s view on these issues? Rorty wants to deny that any brand of “realism” could explain the (apparent?) success of the intentional stance. But since we have already joined Fine and set aside the “metaphysical” problem of realism, Rorty’s reminding us of this only postpones the issue. Even someone who has transcended the scheme/content distinction and has seen the futility of correspondence theories of truth must accept the fact that within the natural ontological attitude we sometimes explain success by correspondence: one does better navigating off the coast of Maine when one uses an up-to-date nautical chart than one does when one uses a road map of Kansas. Why? Because the former accurately represents the hazards, markers, depths, and coastlines of the Maine coast, and the latter does not. Now why does one do better navigating the shoals of interpersonal relations using folk psychology than using astrology? Rorty might hold that the predictive “success” we folk-psychology players relish is itself an artifact, a mutual agreement engendered by the egging-on or consensual support we who play this game provide each other. He would grant that the game has no rivals in popularity, due — in the opinion of the players — to the power it gives them to understand and anticipate the animate world. But he would refuse to endorse this opinion. How, then, would he distinguish this popularity from the popularity among a smaller coterie of astrology? It is undeniable that astrology provides its adherents with a highly articulated system of patterns that they think they see in the events of the world. The difference, however, is that no one has ever been able to get rich by betting on the patterns, but only by selling the patterns to others.

Rorty would have to claim that this is not a significant difference; the rest of us, however, find abundant evidence that our allegiance to folk psychology as a predictive tool can be defended in coldly objective terms. We agree that there is a real pattern being described by the terms of folk psychology. What divides the rest of us is the nature of the pattern, and the ontological implications of that nature.

Rorty is altogether too lenient to non-scientific discourse.

Dennett is primarily concerned about defending the position that beliefs are real. This is part of his broader defense of folk psychology and the intentional stance. I’m omitting this aspect of the paper in order to not over-index on debates in the philosophy of mind.

If R(m) = 0, then either m is our baseline model or m can be interchanged with our baseline model. This interchangeability reminds me of Wittgenstein in the Tractatus, proposition 6.341: “Let us imagine a white surface with irregular black spots. We now say: Whatever kind of picture these make I can always get as near as I like to its description, if I cover the surface with a sufficiently fine square network and now say of every square that it is white or black. In this way I shall have brought the description of the surface to a unified form. This form is arbitrary, because I could have applied with equal success a net with a triangular or hexagonal mesh. It can happen that the description would have been simpler with the aid of a triangular mesh; that is to say we might have described the surface more accurately with a triangular, and coarser, than with the finer square mesh, or vice versa, and so on.”