Dying Atheists

Some anecdotes

I’ve been thinking about stories of atheists dying, and will present some here.

J.B.S. Haldane

Haldane was a colorful figure. His protégé John Maynard Smith tells a story about him that I like:

So we got into this car at the bottom of Parliament Hill. It was a typical Haldane possession— it was extremely old and ramshackle and decrepit. We started driving up the hill, and about halfway up the hill the car started filling with smoke, and I didn’t like to say anything and thought this is normal. But Pamela said “Prof, I think the car’s on fire”. “OH? VERY WELL,” and so we drew up beside and piled out, and as an engineer I was told to find out what was wrong. It was clear nothing very serious went wrong. What had happened was the carpeting had fallen down on the transmission and was burning underneath the front-seat. And Haldane said, “the ladies will go and stand beyond yonder lamppost.” And I thought, oh what next? He then turned to me and said, “Smith. The method of Pantagruel. You have had more beer than I have. Put it out!”

[Laughter]

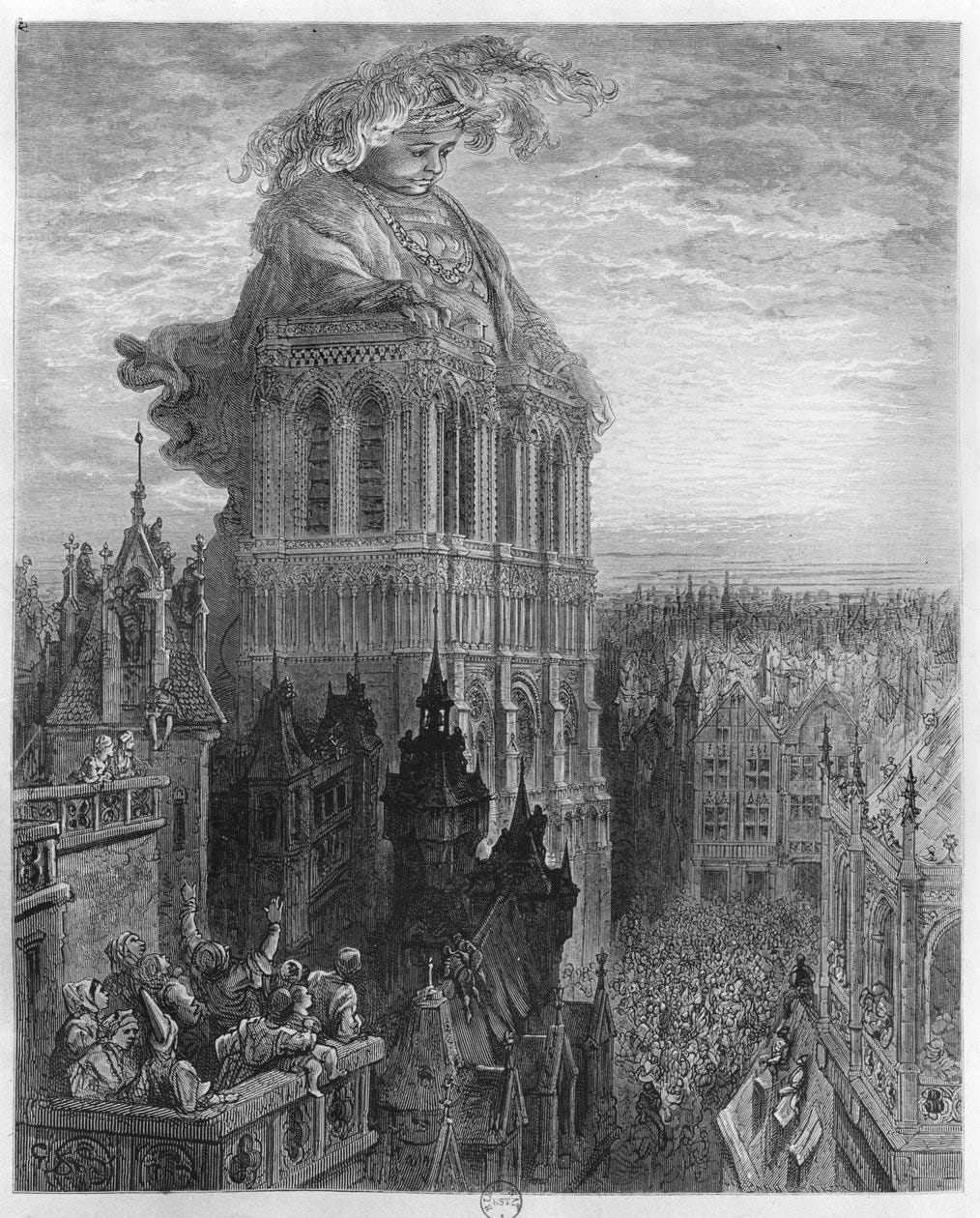

Now part of this is you had to know the classical quotation. You had to know that in fact Pantagruel put out Paris on fire by peeing on it. So I did! I don’t know what you know, but if you’ve had a lot of beer and you start peeing, it’s hard to stop. He went, “that’s enough boy, that’s enough!”

Smith tells another Haldane story, this time about dying:

This was when he was in hospital. He came — it was after he gone to India but he'd come back to visit the West and he'd been having bleeding from the bowel. And he was due to have a major operation. A colostomy. To understand the story you have to realize that a colostomy is an operation in which they give a new opening to your bowels and lower stomach. I went to spend the last half-hour with him before he was wheeled off into… His wife was in India still and I felt that he’d like to have a friend with him one day before he was taken away. They take you away and they shave you around the private parts and they wash you and so on. He's taken away by this nice nurse and brought back in again, and there was a slightly odd expression on his face and I thought but didn't know what was on. But what had obviously happened he decided that possibly— you know he was an old man he might die on the operating table— it was— he was very vain you must understand it was quite important that he has some good last words, and who better to say them to than Smith who would remember them and repeat them. So he looked me straight in the eye said, “WELL SMITH. JUST HAD ME LAST SHIT”. [Laughter] And he wouldn't say another word.

Unfortunately in a sense for him, they weren't his last words and I don't actually know what his last words were. Though I have heard from Helen that as he lay dying in India he had in his hand a stone which he had picked up in Israel in the stream where David is said to have picked up his stone that he used to kill Goliath and apparently he was holding this stone.

[Smith weeps]

I’m so sorry... He was holding this stone as he lay dying and Helen said, “When he dropped it I knew he died”. But I don't know what he last said. Yeah… the world won't be the same without him, but we all have teachers.

William D. Hamilton

In My Intended Burial And Why, William Hamilton relates a number of stories concerning his love of entomology (and, in particular, coleoptery).

There seem to be people incurably fascinated by insects. I am one of them. The interest arises untaught in infancy and harsh experiences of childhood seem to do little to change it. I remember a walk to a wild blackberry patch just after the war and my mother teaching one of my sisters not to be scared of the spiders that were common on huge orb webs among the blackberries. Our big garden Araneus loves to build right in front of the best, ripest berries, as if it knows that these are good places to catch flies. Of course, the webs often intercepted our hands as well. The spiders, however, were never aggressive; when disturbed they would run and hide among leaves. But they were fat and looked—well, spidery, and quite off putting even to me. My mother on this occasion set a spider to walk on her hand; then she encouraged my sister to do the same. I was impressed. Shortly, I too picked one out of its web and placed it on my hand: it walked a few paces, then bit me quite painfully. My old caution returned, but I think my admiration for the courage of the tiny creature only increased: what human would dare stab a giant of equal proportion, even if the giant had just ruined your home? Another time it was not curiosity that caused me to be hurt but simply trying to be kind. A bumblebee stung the finger on which I lifted it, perhaps clumsily, out of a pond where it was drowning. That must have been earlier than the spider incident because we were evacuated to Edinburgh, avoiding the German flying bombs that fell around our home in Kent. From this event, I began to understand that the real world of animals might be fairly different from the world of Aesop’s fables; but the huge furry and stripy insects going to and from their hole in the back masonry wall of the garden pond continued to fascinate me. I smell the stale water and the damp and dark leaf-sodden corner of that Edinburgh garden to this day: the corner held the first bumblebee nest that I ever found.

Foolishly regardless of risks she was creating to my economic success in later life (for though rich men sometimes later become good amateur entomologists, those drugged too early by the fascination of insects seldom become rich), or more likely simply contemptuous of the risks, my mother encouraged my interests. Tirelessly she provided the jam jars for the caterpillars that I brought in and as tirelessly with her hairpins punctured air holes in their paper lids. Tirelessly also she tried not to mind my regular overturning of the stones of her rock garden in my search for beetles and whatever other strange creepies might lurk beneath them.

Stone turning—that, as it now occurs to me, is a trait that might almost define us compulsive juvenile entomologists. We are turners over of junk in waste places, pullers of loose bark from rotting logs. You never know what you may find, the rosy or greenish worm, the spilled-rice confusion of pupae of an ant nest, the sinister dark and yet glorious iridescence of a ground beetle {Carabus violaceus}. Other more vertebrate prizes were not to be neglected either. Under a piece of old corrugated iron half buried in grass may lurk not only these but a mouse nest full of babies or best of all a glossy, sinuous slow worm {European legless lizard}. In my case stone turning accidentally led also in a more dangerous direction. This began when a big flint pulled out of a bank revealed not the expected scurry of insects but rusting tins that had been pushed down a rabbit burrow. Real treasure at last or at least hidden food, I thought, even better than insects; but the tins had only sugary and salty substances in them, and one had aluminium powder which coloured everything it touched silvery grey. They turned out to be the ingredients for explosives that my father, who had experimented new designs for hand grenades for the British Home Guard in the war, had hidden there. The tins were of course taken away from me but I did not fail to notice where they went— this time to a high shelf of our shed. Later I took up the question of what the mysterious ‘ingredients’ could be mixed to make. The answers to this question very soon nearly ended my life and I came back to entomology with shorter fingers and, for a long time, a dull pain in the back and front of my chest.

Did baboon-like hominid ancestors on the high plains of Africa already take advantage of a diversity of temperament which made some members of each group specialise in spotting the insect meals, the best stones to turn, the best logs to pull apart in the search for the grubs that made part of the ape-humans’ normal diet? Were these specialists supposed to learn and to teach which creatures bit or stung or were poisonous, and which could be grabbed and eaten? Going farther with such speculation, might one suggest not only that this natural variation was already present but also that, as the more advanced ancestors of all mankind spread out from Africa over the rest of the world, some sifting of such temperaments, perhaps by chance, happened to send a rather higher proportion of the stone-turning biotype to the East than to the West? It seems to me that the very fact of existence of the magazine for which I write this article indicates a higher proportion of the stone-turning fraternity to be now living upon Asia’s Eastern fringes than on her Western. In other words it is my impression that in Japan there is less of a human divergence in attitudes about insects and fewer examples of the almost hysterical dislike and fear which is quite common in Britain. Here most people wince and draw back at what is seen under a stone, they stamp on the stag beetle that flies uninvited into the garden party. From books, from the live insects, and from the cages for them that are sold in Japanese shops, as well as from the insect-related incidents that I have seen in the streets of Japan and could never imagine in Britain—a man catching cicadas from a tree for a small girl, using a long net on a busy suburban street, small children beside a shrine netting dragonflies, for which they have brought with them a plastic and manufactured cage—I judge that most or all Japanese children must be brought up (or may simply grow up) with a moderate liking for insects. The rather common portrayal of insects and insect-damaged leaves in the art of the Far East, rare to see in Western art, seems to point the same way.

In Europe, to be fated to join the sparse company of stone turners, or to grow up to be a runner after butterflies, is to become an oddity among your schoolfellows, almost a figure of ridicule. In spite of this I doubt that many of the afflicted will express regret over their eccentricity, for the rewards are also great. Perhaps foremost is the instant admission to a world where, first as child, then as adult, and finally even as a veteran right until the very failing of sight, no one can be bored.

Hamilton recalls a picturesque and somewhat absurd adventure involving the Chilean Stag Beetle:

I have not personally seen much of the truly exceptional giant insects of dead wood, but I have interested myself occasionally in the middling giants, the ‘stag’ beetles of the family Lucanidae, which are in fact quite closely related to the much less ornate Passalids just mentioned. If the horns, which are actually mandibles in the lucanids, are enlarged in a given species, the males are usually fierce fighters. Some, like the British stag beetle, seem to need the presence of a female to inspire combat, but others, like the extreme Chilean lucanid, Chiasognathus granti, engage any male on sight and fight until one is either thrown completely from the victor’s vicinity or runs away. Charles Darwin (who encountered them but seemingly did not see fighting) was, unusually, wrong about the effectiveness of the seeming ridiculously long, tong-like mandibles of this species, thinking them to be used mainly for display and for charming the females. In nature, the males rather fight for command of the sap flows on the southern beech trees (Nothofagus) where the females come to feed, or else around the massed flowers of an ivy-like tree-climbing Hydrangea where females similarly assemble. The less strong or expert males are wrenched from their footing by their opponents and, by the combination of the long tongs and the long legs of the victor, are held far out over space and simply dropped away from the scene of rivalry. I have not witnessed quite natural tournaments of this kind with my own eyes but I confidently reconstruct them from accounts given by Chileans and from the remnants of a tournament by Chiasognathus and a replay of it that I did witness in Chile.

I had made a hurried trip from the town of Coyhaique, just eastward across the Andes, to Puerto Aisen on its western fiord of the Pacific. I had come to the more forested coastal zone, hopeful to find Chiasognathus as well as other insects. My whole day’s walk and search in the area had been unlucky, but returning towards my bus stop with only few minutes to spare, I at last came upon a tree clothed in the climbing and flowering hydrangea under which a dozen or more male beetles were crawling about on the grass. I had no time to look for the real champion, the triumphant caster-down of the animals I was seeing. He doubtless must have been just out of sight among the bunched flowers above my head. I simply scooped all the beetles I could see from the grass into a polythene bag and ran for my bus. All the way in the bus back to Coyhaique a crackling from the bag in my back pack drew some odd stares from my neighbours. Listening to it myself I felt already that I knew Darwin must be wrong: it did not sound like any mere symbolic fighting. In fact I had seen some of the beetles fall to some quite vicious struggles even as I dropped them into the bag. By the time the bus had brought me to my hotel near the cordilleran pass, my captives had, however, quietened somewhat and outside, a chilly night with threat of frost was coming on. My room in the hotel was small and ill-lit and I was tired so I decided to leave the bag outside where cold would hopefully immobilise everything until morning. I was not hopeful that even when warmed up I would see much now: surely after all that noise on the bus there could not be much fighting spirit left, perhaps not even many live beetles.

By the end of my breakfast next day a brilliant sun was clearing the last traces of frost from the grass of the lawn outside. Taking my bag to the sunniest spot, I tipped all the beetles out on the grass to see what the remnants were and could do. To my pleasure, all the beetles were intact and alive. What they did was very simple and, in hindsight, quite understandable. Sluggish at first with the cold, but soon warming, they all turned on the grass and crawled towards me. Evidently I, looming above, was for them the tree they had fallen from last night, and they had every intention to go up it and to continue their battle for the flowers where doubtless, the females were soon due to arrive. Where they met as they converged towards me across the grass, they fought; as they climbed onto my boots and met there, they fought some more; and finally the few that reached the level of my calf or knee on my trousers fought most fiercely and desperately of all. With loud crackling of their serrate tongs rasped on cuticle they grabbed at one another. Having secured a grip, they endeavoured to wrench their opponent free of his holds and into the air. As I already described, when one succeeded he would reach out with his long legs, hold his struggling victim over empty space, and drop him. Here of course, they fell only a few inches into the grass and undeterred, the larger beetles would quickly repeat the journey to my boots and re-ascend: but when a small one was dropped he seemed to sense the degree of his outmatching, and he would instead run over the grass in some random direction and attempt to fly. What still interests me out of this tournament, and out of a rather similar one that I have conducted with British stag beetles {Lucanus cervus}, is that the overall victor turned out to be not the largest of the beetles, but second largest. Is there then scope for bluffing? Does it sometimes pay, perhaps in the more hopeful early days of mating, when discretion may indeed be a better part of valour, as the proverb puts it, to have more outward size and more awesome mandibles than your opponent, even when these features outreach your strength?

Returning to the subject for this post, Hamilton closes the piece with the titular section on his burial directives:

So instead of rapt and hearkening in the wood shed at home in Britain, you find me prone on the forest floor in Brazil, in the dusk, closely watching something entirely different. What is it? Well, at the moment it seems to be just a dead chicken. What am I doing? You will see in a moment: a heaving has started somewhere beneath the breast feathers of the chicken, as if from being dead, it had suddenly started to try to breathe. This movement, however, works its way down towards the crop. A mound grows bulbous, the feathers spread out. Suddenly bursting from a ragged hole at the base of the chicken’s neck comes something shiny and green, grotesquely curvaceous, messy—a huge rotund insect, big as a golf ball, sparkling its vivid cuticle from under the blood and flesh and worse kinds of muck that cover its surface in the most glorious gold, yellow and green, as shown in the light of my torch. It has a long black horn sweeping back from its head across a thorax scooped as concave as most beetles have them convex, a full bull-dozer blade of hard body, glossy-metallic chitin warped as if into a phantasy sculpture by Henry Moore. As he—for this one is the male—pushes swiftly down through the feathers to the ground, his messy covering seems to slip lightly from his shoulders, like the disguise of crude clothing slipping from a king who has pretended to be a workman. In a moment, most of him is as resplendent and perfect as a cetoniine chafer daintily climbing down from a flower. There is, however, one thing that perhaps spoils his beauty and makes him a workman still—but also makes him far more interesting in my eyes because such male behaviour is so rare—the big pink ball of flesh, a good human mouthful and half his own size, that he is still carrying in his arms. Where is he taking it? I hold my breath and hardly notice the first heavy drops of the evening storm that are beginning to thump on my back. It is not often I get a chance to see all this, and usually the transactions about to be described take place in darkness beneath the chicken. My eye catches another movement; it is in the dead leaves and the mounds of loose fresh clay piled at the side, a pile thrown up as if by a mole. A moment later and the female is coming out to meet him, head and thorax bursting from her own less bloody hole in the soil. Is she the smaller, rounder, duller being which, as female, whether of horned lucanid, dynastine or scarab, she ought to be, her horns mere shadows and lumps and bumps of her surface, in comparison to those of her mate? No! This one is as large—in fact larger—than the male. A superb horn sweeps even further back over her body, which itself is glinting in the light of my torch, quite as brilliantly as the other. Only perhaps at the extremities of the raised and forked boss of the thorax where the horn can rest, may one judge it to be a little less flared and extravagant. But see, she’s in a hurry, or else she doesn’t like my torch: she almost snatches at the load of meat that the male holds out to her and backs with it instantly into the dark hole she came from. Who does she fight with that horn of hers? What does she fight for? We don’t yet exactly know; so far the many minor skirmishes prior to such (temporary?) pairings as I describe seem to be quite unisex, all against all. Once again, the beetles are abreast of the fashion.

But now the male too has gone under the feathers again and the cold rain comes down on me in a torrent.

Soaked, I hurry to my dinner in the open iron-roofed canteen of Reserva Ducke. It is chicken here too—fried, of course—but I am thinking more of the mysteries of the forest undertakers I have been watching, and their chicken. Of how they sometimes bury their carcass entire, as a team, several pairs together, while other times, even though quite as many are present, they work to remove its flesh on the surface in the way I have described. When they work together, are they all siblings or cousins? Could they know about this?… Shivering a little, I think of how, by the time I am old, all these secrets of their work will be known, of how easily, then, we will super-attract beetles, if we care to, from large areas of forest by means of foetid chemicals… I think how, by that time, I will confidently arrange what I have thought of. I will leave a sum in my last will for my body to be carried to Brazil and to these forests. It will be laid out in a manner secure against the possums and the vultures, just as we make our chickens secure; and this great Coprophanaeus beetle will bury me. They will enter, will bury, will live on my flesh; and in the shape their children and mine, I will escape. No worm for me nor sordid fly, I will buzz in the dusk like a huge bumble bee. I will be many, buzz even as motorbikes, be borne, body by flying body out into the great Brazilian wilderness beneath the stars, lofted under those beautiful and un-fused elytra which we will all hold over our backs. So, finally, I too will shine like a violet ground beetle under a stone.

Hamilton’s body was not conveyed to Brazil, but was in fact buried outside of Oxford. At his memorial service in the Chapel of New College Oxford, an anthem was sung called “Happy is the man that findeth wisdom”, which was originally composed for the funeral of Charles Darwin in 1882. Jerry Coyne’s blog contains a description of Hamilton’s grave.

Derek Parfit

In Part 3 of Reasons and Persons, philosopher Derek Parfit meditates on the problem of personal identity, and through thought experiments such as teletransportation and split-brain cases he concludes that one should adopt a reductionist view of personal identity. When he died, the following extract from Reasons and Persons was widely shared:

13 What Does Matter

95 Liberation from the Self

The truth is very different from what we are inclined to believe. Even if we are not aware of this, most of us are Non-Reductionists. If we considered my imagined cases, we would be strongly inclined to believe that our continued existence is a deep further fact, distinct from physical and psychological continuity, and a fact that must be all-or-nothing. This is not true. Is the truth depressing? Some may find it so. But I find it liberating, and consoling. When I believed that my existence was a such a further fact, I seemed imprisoned in myself. My life seemed like a glass tunnel, through which I was moving faster every year, and at the end of which there was darkness. When I changed my view, the walls of my glass tunnel disappeared. I now live in the open air. There is still a difference between my life and the lives of other people. But the difference is less. Other people are closer. I am less concerned about the rest of my own life, and more concerned about the lives of others.

When I believed the Non-Reductionist View, I also cared more about my inevitable death. After my death, there will no one living who will be me. I can now redescribe this fact. Though there will later be many experiences, none of these experiences will be connected to my present experiences by chains of such direct connections as those involved in experience-memory, or in the carrying out of an earlier intention. Some of these future experiences may be related to my present experiences in less direct ways. There will later be some memories about my life. And there may later be thoughts that are influenced by mine, or things done as the result of my advice. My death will break the more direct relations between my present experiences and future experiences, but it will not break various other relations. This is all there is to the fact that there will be no one living who will be me. Now that I have seen this, my death seems to me less bad.

Instead of saying, ‘I shall be dead’, I should say, ‘There will be no future experiences that will be related, in certain ways, to these present experiences’. Because it reminds me what this fact involves, this redescription makes this fact less depressing. Suppose next that I must undergo some ordeal. Instead of saying, ‘The person suffering will be me’, I should say, ‘There will be suffering that will be related, in certain ways, to these present experiences’. Once again, the redescribed fact seems to me less bad.

I can increase these effects by vividly imagining that I am about to undergo one of the operations I have described. I imagine that I am in a central case in the Combined Spectrum, where it is an empty question whether I am about to die. It is very hard to believe that this question could be empty. When I review the arguments for this belief, and reconvince myself, this for a while stuns my natural concern for my future. When my actual future will be grim—as it would be if I shall be tortured, or shall face a firing squad at dawn—it will be good that I have this way of briefly stunning my concern.

After Hume thought hard about his arguments, he was thrown into ‘the most deplorable condition imaginable, environed with the deepest darkness’. The cure was to dine and play backgammon with his friends. Hume's arguments supported total scepticism. This is why they brought darkness and utter loneliness. The arguments for Reductionism have on me the opposite effect. Thinking hard about these arguments removes the glass wall between me and others. And, as I have said, I care less about my death. This is merely the fact that, after a certain time, none of the experiences that will occur will be related, in certain ways, to my present experiences. Can this matter all that much?

A decade later, Parfit revisits this argument in his essay The Unimportance of Identity. The essay is short, self-contained, and clear, and can be read in its entirety by someone with little interest in philosophy. In the closing paragraph, Parfit says:

Even the use of the word 'I' can lead us astray. Consider the fact that, in a few years, I shall be dead. This fact can seem depressing. But the reality is only this. After a certain time, none of the thoughts and experiences that occur will be directly causally related to this brain, or be connected in certain ways to these present experiences. That is all this fact involves. And, in that redescription, my death seems to disappear.

These attitudes were not nominal in Parfit. In David Edmonds’ biography Parfit, many stories are supplied which illustrate his idiosyncratic posture towards the dead. He did not seem to care that much about his own death, except for the very alarming fact that his death would prevent him from completing his work establishing the groundwork for moral realism. He was, however, very distressed by the deaths of others. His ability to feel the deaths of others reached a level of abstraction that few of us share:

Meanwhile, with the Schock ceremony still a few months away, Parfit was back to work. A University of Warwick philosopher, Victor Tadros, visited him at his Oxford home in February 2014. They discussed whether the intention with which an act is done could make that act wrong. Might an act done with a good intention be acceptable, while the same act carried out with a bad intention be wrong? Tadros thought so—Parfit disagreed. Four hours after they began talking, at about 6 p.m., Tadros needed food, and so they headed to a Lebanese restaurant in the Jericho district, talking philosophy all the while. Debate continued throughout the meal, when the subject of World War I came up.

Suddenly, in the middle of that discussion, Derek started to cry, really quite a bit. He was crying at the sadness of all of those lives ended prematurely in the war. I wasn’t quite sure what to make of this. Did Derek have an admirable connection with human beings whose lives were distant from our own in time that most of us, including me, lack? I found that kind of reaction really odd, and, yes, in a way admirable. Thinking about it later, I wasn’t sure whether it was compatible with the kind of deep interaction that most people hope to have with some particular people—their families and close friends. His reaction to those who lost their lives in World War I was a bit like the reaction that a person would have during a discussion of a close friend or family member who had recently passed. And so perhaps there was something admirable about it, but [. . .] this might come at a price—the price of the distinct personal relations that we have with those who are special to us.

Indeed, Parfit’s consequentialism, and the view that we should not draw a sharp distinction between strangers on the one hand, and our nearest and dearest on the other, may have been the product of his rational philosophical reasoning, but it was relatively easy for him to embrace, because it chimed with his atypical emotional reactions. His sensibility with regard to suffering was constrained by neither time nor place.

…

Parfit’s talk in Stockholm came last, and everyone remembers it in much the same way. He was pacing up and down, and because the stage was so brightly lit, and the audience was in near-darkness, it was nigh impossible to make out the edge of the platform. Several times, he came perilously close to tumbling of. Then, towards the end of his talk, he mentioned Johann Sebastian Bach’s last and unfinished work, The Art of Fugue—he did so just as an aside, in raising the possibility that there might be some higher or superior values, such that some amount of these values is to be preferred to any amount of an inferior value: one composition by Bach, for example, might be considered of greater value than ten thousand songs by Barry Manilow. But there was also the problem known as ‘lexical imprecision’: it might be impossible to say whether Bach was superior to Wagner.

Mid-paper, and quite suddenly, Parfit stopped talking and began to cry. Not just moistening of the eyes, but full-on weeping. And not for just a few seconds—it went on for around a minute and a half. There were approximately a hundred people in the audience, and there was some uncomfortable shuffling in seats, with people not knowing where to look or how to react. Eventually, Parfit managed to pull himself together, apologize, and carry on.

Wlodek Rabinowicz and Parfit were staying in the same hotel, and the following day, Rabinowicz questioned him about it: ‘Why did you cry?’ ‘It’s such a beautiful piece of music’, Parfit replied, ‘and it is so tragic that Bach died before he could complete it.’ And then he began to cry all over again.

Parfit was affected in this way by the deaths of friends and colleagues:

As people age, it is no doubt natural for them to reflect more on death. The body weakens and wilts, more friends and contemporaries die. Isaiah Berlin passed away in November 1997. Bernard Williams died in 2003, Susan Hurley in 2007, Patricia Zander in 2008, Jerry Cohen in 2009, and Ronnie Dworkin in 2013. Parfit was, to varying degrees, affected by each loss. About a month after Williams’s death, his widow Patricia was invited to dinner at All Souls. She was placed next to Parfit, and when talk turned to Bernard, Parfit immediately burst into tears. ‘I ended up comforting him. Only afterwards did I realize how strange this was.’ At Jerry Cohen’s funeral, Jerry’s daughter Miriam reminded Parfit that he had once rung Cohen to check whether it was acceptable to describe Jerry as a friend. Parfit began to weep.

Aided by his philosophy, Parfit had gone some way to accommodate himself to mortality. Sally Ruddick, the wife of his old friend Bill, passed away in 2011, and Derek sent a note to Bill on 27 June, as soon as he heard the news.

When I think of someone dead whom I loved, it helps me to remember that this person isn’t less real because she isn’t real now, just as people far away aren’t less real because they aren’t real here. But it’s awful to know that Sally isn’t real now.

…

As it happens, Parfit had sent an almost identical message of condolence to the writer Joyce Carol Oates when her first husband, Raymond Smith, died. ‘I am very sorry to learn that Ray died a couple of weeks ago. When someone I loved died I found it helpful to remind myself that this person was not less real because she was not real now, just as people in New Zealand aren’t less real because they aren’t real here.’ Parfit had become acquainted with the Princeton-based author through his friend Jeff McMahan, and she had attended several of his lectures. Oates was grateful for his good wishes, and sufficiently moved to reproduce the note in a book she published about her grief; but privately, she too was unconvinced that Parfit’s suggestion provided much solace. She compared it to trying to console an amputee that his leg was still real and existed in New Zealand.

In 2014, Parfit’s lung collapsed, and his life was saved by the swift action of Jeff McMahan. Parfit did not seem personally shaken by the experience:

At the hospital, one of the nurses requested Parfit’s permission to intubate him. He was unresponsive; his breathing was extremely shallow and rapid. McMahan told him to nod to indicate permission, but there was still no reaction. The medical staff hastily ushered McMahan out. When Parfit’s clothes were eventually returned to him, it became clear that after McMahan had left the room, they had ripped his shirt of, not bothering to unbutton it.

He was put under a general anaesthetic and was still unconscious the following day, when McMahan returned. Emerging finally from unconsciousness with a tube in his throat, he couldn’t speak, but he gestured for a pad and a pen. ‘He didn’t ask, “Where am I, what’s happening to me, what’s my condition?” He didn’t ask, “Am I going to live?” He wrote that he was supposed to be on Johann Frick’s thesis committee—and he needed to go to Harvard for his viva.’ Frick was one of Parfit’s doctoral students. It had to be explained to Parfit that he would not be able to fulfill this obligation.

Temkin went to see Parfit that day. ‘It was frightening. He was haggard. He had whiskers. He looked like hell.’ He still wanted to philosophize, but had to communicate in writing. When he was eventually taken of the ventilator, it was painful for him to talk, and his voice was raspy. That did not deter him. Frick’s viva would have to go ahead without Parfit, though Parfit had written to the examiners suggesting a postponement: ‘I’m sorry for these typos, but I’m having to type only one bandaged ffinger. Affextionately Derek.’ After Parfit had been in hospital for a few days, Frick was given the green light to visit him: ‘He was still in intensive care, with tubes coming out of him, and I stuck my head through the door. Derek saw me and literally his first words were, “Johann, so good of you to come. I’ve only read your dissertation twice so far, but I have some questions.” He gave me a two-or-three-hour viva, which was much tougher than anything I had a few days later.’