Peering into Hell

Some unstructured thoughts about hell and enjoying seeing people in it

The Two Lazaruses

In the gospel of Luke, Jesus tells the story of the rich man and Lazarus1:

There was a certaine rich man, which was clothed in purple and fine linnen, and fared sumptuously euery day.

And there was a certaine begger named Lazarus, which was layde at his gate full of sores,

And desiring to bee fed with the crummes which fel from the rich mans table : moveouer the dogges came and licked his sores.

And it came to passe that the begger died, and was caried by the Angels into Abrahams bosome : the rich man also died, and was buried.

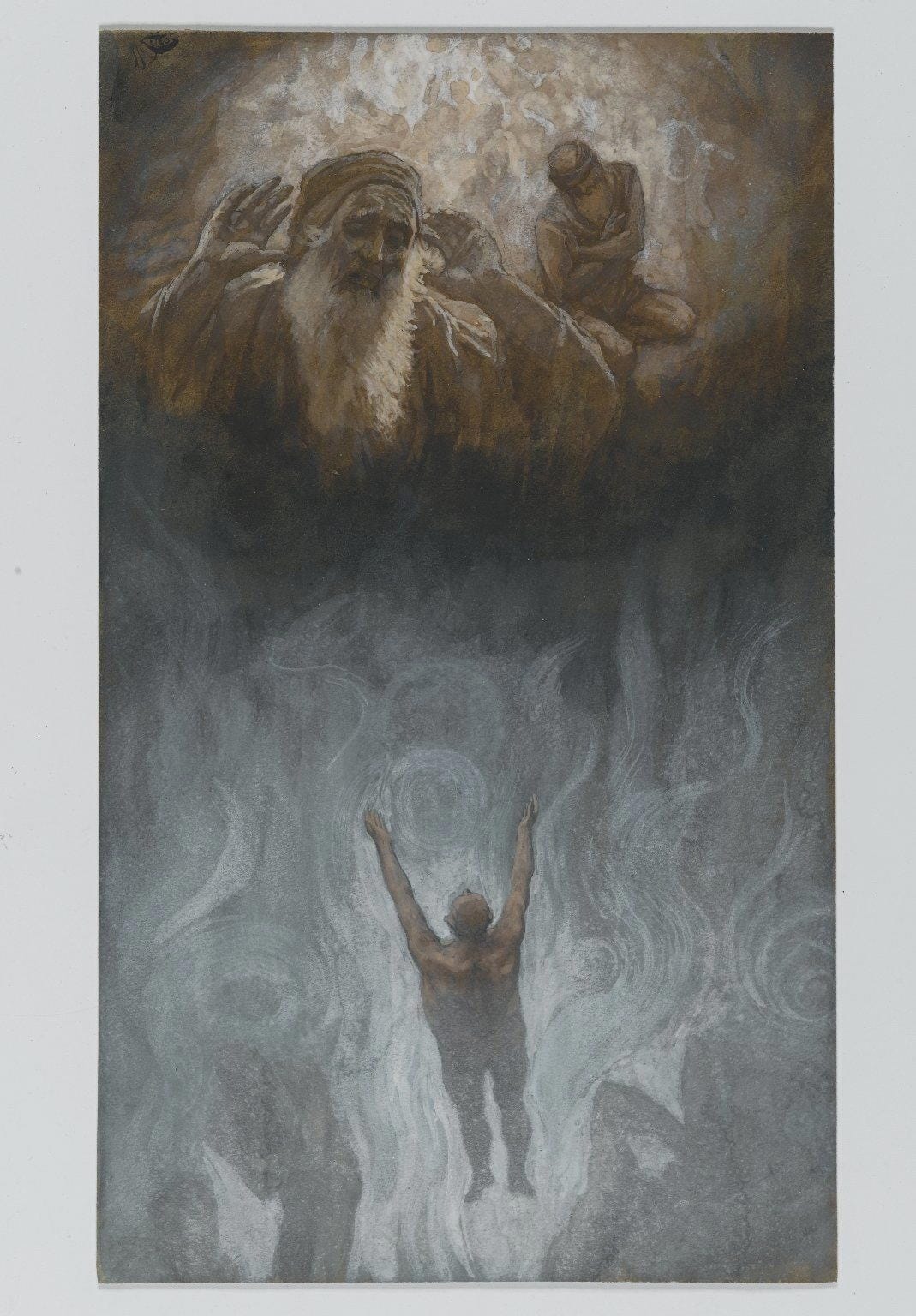

And in hell he lift vp his eyes being in torments, and seeth Abraham afarre off, and Lazarus in his bosome :

And he cried, and said, Father Abraham, haue mercy on mee, and send Lazarus, that he may dip the tip of his finger in water, and coole my tongue, for I am tormented in this flame.

But Abraham saide, Sonne, remember that thou in thy life-time receiuedst thy good things, but now he is comforted, and thou art tormented.

And besides all this, betweene vs and you there is a great gulfe fixed, so that they which would passe from hence to you, cannot, neither can they passe to vs, that would come from thence.

Then he said, I pray thee therefore father, that thou wouldest send him to my fathers house :

For I haue fiue brethren, that he may testifie vnto them, lest they also come into this place of torment.

Abraham saith vnto him, They haue Moses and the Prophets, let them heare them.

And hee said, Nay, father Abraham: but if one went vnto them from the dead, they will repent.

And hee said vnto him, If they heare not Moses and the Prophets, neither will they be perswaded, though one rose from the dead.(Luke 16:16-31, 1611 KJV)

So the rich man begs that Lazarus be sent from heaven to relieve him of his suffering, but Abraham will not and cannot comply because the “great gulf” between those in heaven and those in hell is unfordable. Then the rich man man asks that Lazarus be resurrected and sent to his brothers to induce them to repent, but Abraham will not do this, reasoning that it would be pointless since they already had exposure to the teachings of Moses and the other prophets and would have already repented if they could.

I don’t understand why people think fallacious nonsense like this is wise. Clearly you would find the resurrection of someone you knew persuasive evidence of a divine order, even— or perhaps especially if— you found the testimony of prophets long dead to be wanting. It is especially puzzling that Jesus would tell a story like this, because in the gospel of John we see Jesus using the resurrection of the other Lazarus in exactly this way. While it may be argued that Jesus resurrected Lazarus of Bethany due to sympathy2, it is clear that it brought many to the faith:

And when hee thus had spoken, he cryed with a loude voice, Lazarus, come forth.

And he that was dead, came forth, bound hand & foot with graue-clothes: and his face was bound about with a napkin. Iesus saith vnto them, Loose him, and let him goe.

Then many of the Iewes which came to Mary, and had seene the things which Iesus did, beleeued on him.(John 11:43-45, 1611 KJV)

Much people of the Iewes therefore knew that [Jesus] was there : and they came, not for Iesus sake onely, but that they might see Lazarus also, whom he had raised from the dead.

But the chiefe Priests consulted, þt3 they might put Lazarus also to death,

Because that by reason of him many of the Iewes went away and beleeued on Iesus.(John 12:9-11, 1611 KJV)

Aquinas on the Pleasures of Observing the Damned

In the supplement to the third part of his Summa Theologica, Thomas Aquinas proves that those in heaven observe the punishment of the damned, and that not only do they not pity them, they actively enjoy their suffering:

Article 2. Whether the blessed pity the unhappiness of the damned?

Objection 1. It would seem that the blessed pity the unhappiness of the damned. For pity proceeds from charity; and charity will be most perfect in the blessed. Therefore they will most especially pity the sufferings of the damned.

Objection 2. Further, the blessed will never be so far from taking pity as God is. Yet in a sense God compassionates our afflictions, wherefore He is said to be merciful.

On the contrary, Whoever pities another shares somewhat in his unhappiness. But the blessed cannot share in any unhappiness. Therefore they do not pity the afflictions of the damned.

I answer that, Mercy or compassion may be in a person in two ways: first by way of passion, secondly by way of choice. In the blessed there will be no passion in the lower powers except as a result of the reason's choice. Hence compassion or mercy will not be in them, except by the choice of reason. Now mercy or compassion comes of the reason's choice when a person wishes another's evil to be dispelled: wherefore in those things which, in accordance with reason, we do not wish to be dispelled, we have no such compassion. But so long as sinners are in this world they are in such a state that without prejudice to the Divine justice they can be taken away from a state of unhappiness and sin to a state of happiness. Consequently it is possible to have compassion on them both by the choice of the will—in which sense God, the angels and the blessed are said to pity them by desiring their salvation—and by passion, in which way they are pitied by the good men who are in the state of wayfarers. But in the future state it will be impossible for them to be taken away from their unhappiness: and consequently it will not be possible to pity their sufferings according to right reason. Therefore the blessed in glory will have no pity on the damned.

Reply to Objection 1. Charity is the principle of pity when it is possible for us out of charity to wish the cessation of a person's unhappiness. But the saints cannot desire this for the damned, since it would be contrary to Divine justice. Consequently the argument does not prove.

Reply to Objection 2. God is said to be merciful, in so far as He succors those whom it is befitting to be released from their afflictions in accordance with the order of wisdom and justice: not as though He pitied the damned except perhaps in punishing them less than they deserve.

Article 3. Whether the blessed rejoice in the punishment of the wicked?

Objection 1. It would seem that the blessed do not rejoice in the punishment of the wicked. For rejoicing in another's evil pertains to hatred. But there will be no hatred in the blessed. Therefore they will not rejoice in the unhappiness of the damned.

Objection 2. Further, the blessed in heaven will be in the highest degree conformed to God. Now God does not rejoice in our afflictions. Therefore neither will the blessed rejoice in the afflictions of the damned.

Objection 3. Further, that which is blameworthy in a wayfarer has no place whatever in a comprehensor. Now it is most reprehensible in a wayfarer to take pleasure in the pains of others, and most praiseworthy to grieve for them. Therefore the blessed nowise rejoice in the punishment of the damned.

On the contrary, It is written (Psalm 57:11): "The just shall rejoice when he shall see the revenge."

Further, it is written (Isaiah 66:24): "They shall satiate the sight of all flesh." Now satiety denotes refreshment of the mind. Therefore the blessed will rejoice in the punishment of the wicked.

I answer that, A thing may be a matter of rejoicing in two ways. First directly, when one rejoices in a thing as such: and thus the saints will not rejoice in the punishment of the wicked. Secondly, indirectly, by reason namely of something annexed to it: and in this way the saints will rejoice in the punishment of the wicked, by considering therein the order of Divine justice and their own deliverance, which will fill them with joy. And thus the Divine justice and their own deliverance will be the direct cause of the joy of the blessed: while the punishment of the damned will cause it indirectly.

Reply to Objection 1. To rejoice in another's evil as such belongs to hatred, but not to rejoice in another's evil by reason of something annexed to it. Thus a person sometimes rejoices in his own evil as when we rejoice in our own afflictions, as helping us to merit life: "My brethren, count it all joy when you shall fall into divers temptations" (James 1:2).

Reply to Objection 2. Although God rejoices not in punishments as such, He rejoices in them as being ordered by His justice.

Reply to Objection 3. It is not praiseworthy in a wayfarer to rejoice in another's afflictions as such: yet it is praiseworthy if he rejoice in them as having something annexed. However it is not the same with a wayfarer as with a comprehensor, because in a wayfarer the passions often forestall the judgment of reason, and yet sometimes such passions are praiseworthy, as indicating the good disposition of the mind, as in the case of shame pity and repentance for evil: whereas in a comprehensor there can be no passion but such as follows the judgment of reason.

So, the blessed will not rejoice in the punishment of the damned in itself, but will rejoice in the thing that is (necessarily) connected to the punishment of the damned (viz. the execution of God’s justice). This sort of distinction is very typical for Aquinas. It is related to a similar distinction he made that I've mentioned before: the Doctrine of Double Effect, which is the supposed moral principle that there is an ethical distinction between intending for a bad effect to result from your actions and merely foreseeing that a bad effect results from your actions. It is unpersuasive to me that the punishment of the damned is a distinct thing from God’s justice, as the former is necessarily a part of the latter (to be “damned” and “punished” is to be subject to God’s justice necessarily), and therefore these two concepts are related as a part is to the whole. So there is no way to avoid rejoicing in the punishment of the damned directly while rejoicing in God’s justice in general: to not rejoice in the punishment of the damned directly is to not directly enjoy a part of God’s justice.

Exaltation & Instruction

Many Christian theologians passionately fantasized about witnessing the torture of the damned. Tertullian, so-called “father of Latin Christianity”, in his tract De Spectaculis enjoys anticipating how the spectacular violence the Roman people were so passionate for will be ironically visited upon them in the afterlife:

Yes, and there are other sights: that last day of judgment, with its everlasting issues; that day unlooked for by the nations, the theme of their derision, when the world hoary with age, and all its many products, shall be consumed in one great flame! How vast a spectacle then bursts upon the eye! What there excites my admiration? What my derision? Which sight gives me joy? Which rouses me to exultation? — as I see so many illustrious monarchs, whose reception into the heavens was publicly announced, groaning now in the lowest darkness with great Jove himself, and those, too, who bore witness of their exultation; governors of provinces, too, who persecuted the Christian name, in fires more fierce than those with which in the days of their pride they raged against the followers of Christ. What world's wise men besides, the very philosophers, in fact, who taught their followers that God had no concern in ought that is sublunary, and were wont to assure them that either they had no souls, or that they would never return to the bodies which at death they had left, now covered with shame before the poor deluded ones, as one fire consumes them! Poets also, trembling not before the judgment-seat of Rhadamanthus or Minos, but of the unexpected Christ! I shall have a better opportunity then of hearing the tragedians, louder-voiced in their own calamity; of viewing the play-actors, much more dissolute in the dissolving flame; of looking upon the charioteer, all glowing in his chariot of fire; of beholding the wrestlers, not in their gymnasia, but tossing in the fiery billows; unless even then I shall not care to attend to such ministers of sin, in my eager wish rather to fix a gaze insatiable on those whose fury vented itself against the Lord.

Two millennia later we find Jonathan Edwards rejoicing in torture in his sermon The End of the Wicked Contemplated by the Righteous:

It will occasion rejoicing in them, as they will have the greater sense their own happiness, by seeing the contrary misery. It is the nature of pleasure and pain, of happiness and misery, greatly to heighten the sense of each other. Thus the seeing of the happiness of others tends to make men more sensible of their own calamities; and the seeing of the calamities of others tends to heighten the sense of our own enjoyments.

When the saints in glory, therefore, shall see the doleful state of the damned, how will this heighten their sense of the blessedness of their own state, so exceedingly different from it! When they shall see how miserable others of their fellow creatures are, who were naturally in the same circumstances with themselves; when they shall see the smoke of their torment, and the raging of the flames of their burning, and hear their dolorous shrieks and cries, and consider that they in the mean time are in the most blissful state, and shall surely be in it to all eternity ; how will they rejoice!

This will give them a joyful sense of the grace and love of God to them; because hereby they will see how great a benefit they have by it. When they, shall see the dreadful miseries of the damned, and consider that they deserved, the same misery, and that it was sovereign grace, and nothing else, which made them so much to differ from the damned, that, if it had not been for that, they would have been in the same condition; but that God from all eternity was pleased to set his love upon them, that Christ hath laid down his life for them, and hath made them thus gloriously happy forever, O how will they admire that dying love of Christ, which has redeemed them from so great a misery, and purchased for them so great happiness, and has so distinguished them from others of their fellowcreatures! How joyfully will they sing to God and the Lamb, when they behold this!

These repugnant sadists are all influential, but their attitude is somewhat exceptional. It is more common to say that the torture of the damned is good for we the living because it is instructive. In the 17th century, a Jesuit named Giovanni Pietro Pinamonti published a tract called Hell Opened to Christians To Caution Them From Entering It, which contained a series of daily meditation exercises focused on imagining the various qualities of Hell. For instance, on Sunday it is recommended to contemplate its stench:

III. Its Stench

Consider how much the misfortunes of this prison, so strait and obscure, must be heightened by the addition of the greatest stench…. The devil being discovered fled away, but left so great a stench behind him that this alone was sufficient for the saint to discover him. If then one single devil could raise such a stench, what will that pestiferous breath be that shall be exhaled in that dungeon, where all the whole crowd of tormenting devils and all the bodies of the tormented will be penned up together. Air itself, being for a time closely shut up, becomes insupportable: judge then what stink of such loathsome filth must be to those that are confined in it forever.

For Saturday we are enjoined to contemplate the eternity of pain:

I. It is Endless

Consider that were the pains of Hell less racking, yet, being never to have an end, they would become infinite. What, then, will it be, they being both intolerable as to sharpness and endless as to duration! Who can conceive how much it adds to grief its being never to have an end! The torment of one hour is a great pain, that of two must be twice as much; the torment of a hundred hours must be a hundred times as much, and so on, the pain still increasing in proportion of the time of its duration. What, then, must that be, which is to last infinite hours, infinite days, infinite ages? That pain certainly must be infinite, and surpass all our thoughts to conceive it…. O eternity, then, O eternity! Either sinners have no faith or no senses! Canst thou deny that living in sin is not exposing thyself to the danger of falling into this abyss, from where there is no getting out forever? Thou canst deny it, if thou are a Christian. But, on the contrary, thou mayest say with truth that by living thus, thou art not above one step off the abyss or, rather, have already one foot in it…. Since, then, we may die at any moment, we may also any moment be lost forever. The exposing ourselves to such evident danger of burning for the space of a thousand years on account of some vile and transitory pleasure would undoubtedly be a very great madness.

Pinamonti notes the trouble with figuring out why finite sins are rewarded with infinite punishment:

III. It is just.

Consider that men reasoning always as men are astonished that God for so short a pleasure of a sinner should have decreed an everlasting punishment in the fire of Hell. Nor do they know how to reconcile in their thoughts this rigor, either with divine goodness, which is so compassionate, or with divine justice, which does not punish beyond reason. But ought not we rather to wonder at the astonishment of worldlings, grounded on the ignorance of spiritual things: “The sensual man does not perceive the things that are of the Spirit of God, for it is a folly to him and he cannot understand.” If sinners did but comprehend the malice of their sin, they would soon change their wonder into one far greater. They are, at present, amazed how God could for one only fault make Hell to be eternal, but when they come into the other world, they will wonder much more that he has not created a Hell and provided pains incomparably more cruel for every transgression…. Consider, therefore that every mortal sin is either a tacit or express contempt of the divine will and an injury to God. Now an injury is increased on two accounts, either by dignity of the person offended or the vileness of the offender. The majesty, therefore, of God being infinite, and our vileness in the lowest degree, it follows that the injury which we do him is in a manner infinite.

In the 19th century, Catholic priest John Furniss4 published a similarly helpful tract called The Sight of Hell, which was written “for children and young persons”:

I. WHERE IS HELL?

Every little child knows that God will reward the good in Heaven and punish the wicked in Hell. Where, then, is Hell? Is Hell above or below? Is it on the earth, or in the earth, or below the earth?

It seems likely that Hell is in the middle of the earth. Almighty God has said that “He will turn the wicked into the bowels of the earth.”

…

XX. A BED OF FIRE

The sinner lies, chained down on a bed of red-hot blazing fire! When a man, sick of fever, is lying on even a soft bed, it is pleasant sometimes to turn round. If the sick man lies on the same side for a long time, the skin comes off, the flesh gets raw. How will it be when the body has been lying on the same side on the scorching, broiling fire for a hundred millions of years! Now look at that body, lying on the bed of fire. All the body is salted with fire. The fire burns through every bone and every muscle. Every nerve is trembling and quivering with the sharp fire. The fire rages inside the skull, it shoots out through the eyes, it drops out through the ears, it roars in the throat as it roars up a chimney. So will mortal sin be punished. Yet there are people in their senses who commit mortal sin!

…

(e) The Fifth Dungeon: The Red-Hot Oven

“You shalt make him as an oven of fire in the time of Thy anger.” You are going to see again the child about which you read in the Terrible Judgment, that it was condemned to Hell. See! It is a pitiful sight. The little child is in this red-hot oven. Hear how it screams to come out. See how it turns and twists itself about in the fire. It beats its head against the roof of the oven. It stamps its little feet on the floor of the oven. You can see on the face of this little child what you see on the faces of all in Hell— despair, desperate and horrible!

The same law which is for others is also for children. If children knowingly and willingly break God’s commandments, they also must be punished like others. This child committed very bad mortal sins, knowing well the harm of what it was doing and knowing that Hell would be the punishment. God was very good to this child. Very likely God saw that this child would get worse and worse, and would never repent, and so it would have to be punished much more in Hell. So, God in His mercy called it out of the world in its early childhood.

In response to filth like this, freethinker Austin Holyoake— speaking on behalf of morality and common-sense— wrote in 1873:

The Bible, or any other book, which teaches the doctrine of Hell torments, is not, cannot be, a revelation from a God of love and mercy. It is the crude production of an ignorant, a superstitious, a priest-ridden, and brutal people. The Bible alone, of all books in the world, first promulgated the monstrous, the fiendish doctrine of eternal, never-ending torments prepared for all men, not one-millionth part of whom ever saw or heard of it. This doctrine, so far from keeping men good, makes good men bad, and brutalizes all who believe in it. It distracts men’s minds from the duties of this life, and deludes them into the belief of another which, when looked at calmly and with reason, will be seen to contain no element worthy of their acceptance, or capable of promoting permanent happiness.

Putting aside the savagery of all this, I am made to wonder why Christians are generally thought to be deontologists. You cannot say that the infinite torture of humans is justified because it provides a useful lesson to other humans. This is to treat humans as a mere means, and so contradicts Kant’s second formulation of the categorical imperative:

Act in such a way that you treat humanity, whether in your own person or in the person of any other, never merely as a means to an end, but always at the same time as an end.

There is also just not any plausible consequentialist calculus that would punish finite malice with infinite torture. It really does seem to me that the majority of Christians de facto follow the dictum of Thrasymachus (which Plato made him say in The Republic): “Listen—I say that justice is nothing other than the advantage of the stronger”. The infinite power of God himself is the only grounds to claim that finite offenses to him can be met with infinite evil. Of course, Christian philosophers will talk about “natural law” or “virtue ethics”, but I think the actual heart of Christian morality does not extend much further than Thrasymachus’ principle.

Universalism

Christian Universalism is the view that all people will be saved eventually. You would think this would be the leading theory today, but it is not. In 2019, David Bentley Hart wrote a book defending universalism called That All Shall Be Saved, a reference to 1 Timothy 2:4 which says God “intends that all human beings shall be saved” (perhaps here a degenerate Thomist would cut in to say that God intends but does not foresee that all humans beings shall be saved). Edward Feser, a professional Smart Christian Philosopher, in his review of the book argues simply: “Not to put too fine a point on it, this is heresy.”

Maybe we’ll be free from this barbarism in a century or two.

Also known traditionally in English as the parable of “Dives and Lazarus”, where the Latin for rich man (dives) is attached to the rich man as his name.

“Iesus wept”. (John 11:35)

that

Yet another instance of nominative determinism?