Vibethinking as Bullshit

Dwarkin' it

In Notes on Honesty, I discussed Harry Frankfurt’s theory of bullshit. This concept is a bit worn out, but I think it will have a second wind of usefulness in the LLM age. Frankfurt asserts:

One of the most salient features of our culture is that there is so much bullshit. Everyone knows this. Each of us contributes his share. But we tend to take the situation for granted. Most people are rather confident of their ability to recognize bullshit and to avoid being taken in by it.

…

Bullshit is unavoidable whenever circumstances require someone to talk without knowing what he is talking about. Thus the production of bullshit is stimulated whenever a person’s obligations or opportunities to speak about some topic are more excessive than his knowledge of the facts that are relevant to that topic.

Keep this observation in mind.

Reinforcement Learning is notorious for its “sample inefficiency”. It is a very data-hungry learning method. Improving sample efficiency is a major area of RL research.

Dwarkesh Patel on Substack published some revelations about sample efficiency in RL. He used information theory to compare the sample efficiency of RL and supervised learning (which is a bit novel in a couple of ways: “sample efficiency” isn’t even common jargon in the supervised learning context). He proposes a mathematical model where the bits/sample of a learning model is a function of the “pass rate” r, which is the probability of a correct guess. In supervised learning, you are told the correct answer, so the model’s surprisal drops to 0 as r tends to 1. Using the formula for entropy, Dwarkesh claims that the sample efficiency of supervised learning is bounded above by:

In reinforcement learning you do not get told the correct label — you only get told you got the correct answer if you reach it. As such you learn little if r is close to either 0 or 1. Dwarkesh claims from this that the sample efficiency of RL is bounded above by:

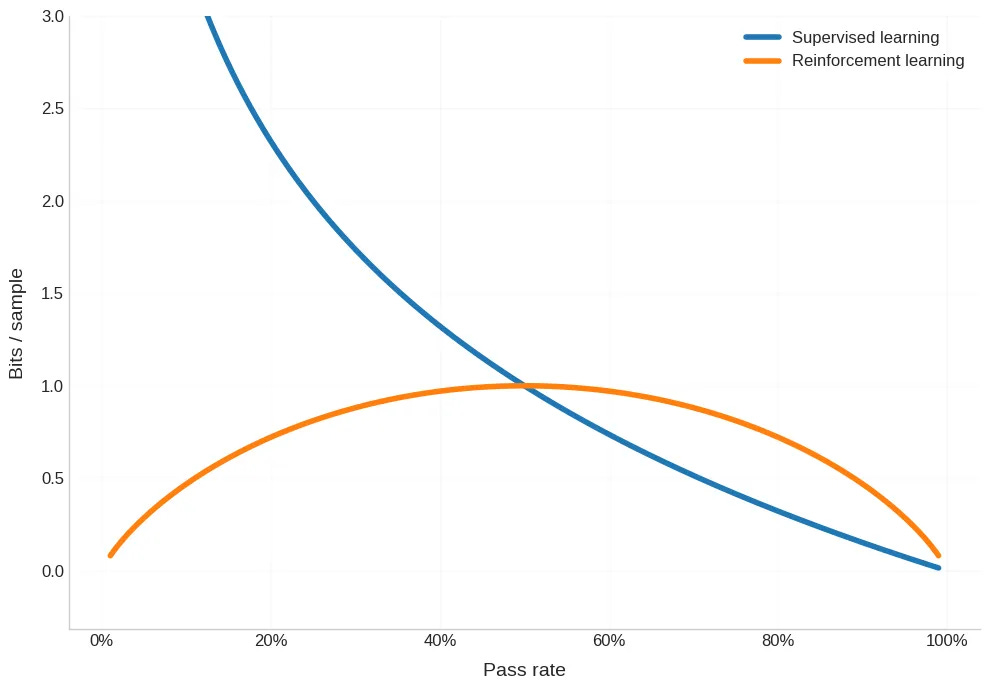

Summarized by this graph:

Here we see the “Goldilocks zone” of reinforcement learning.

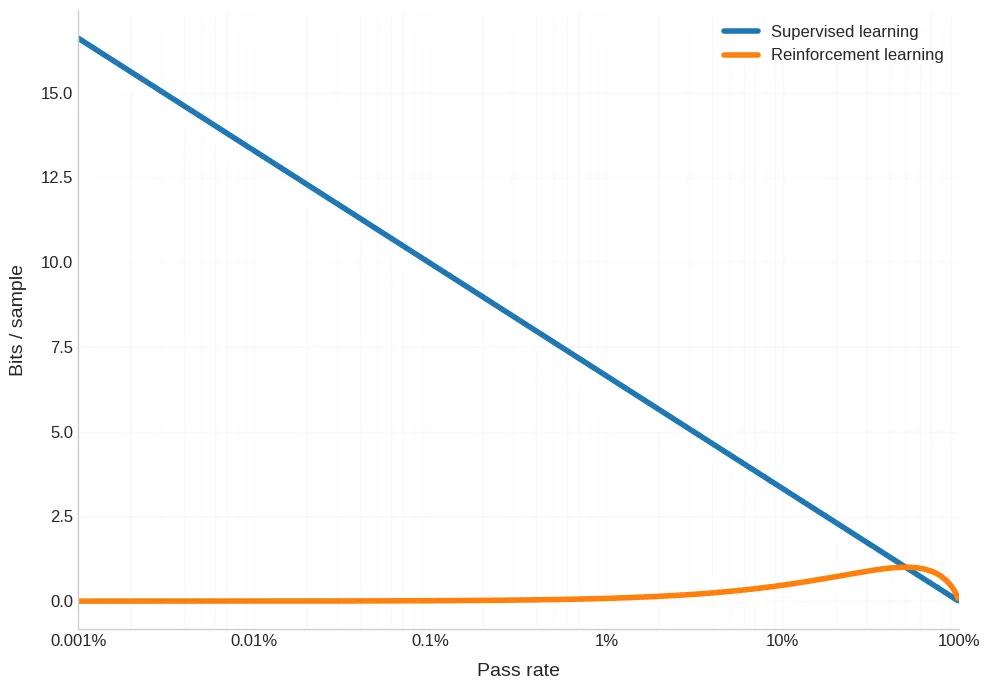

However this graph is misleading because the power laws of scaling, being what they are, suggest that we should be looking at the log of r.

So the “Goldilocks zone” is, in effect, quite small. But the bright side is that Dwarkesh thinks we can build on certain techniques with an eye towards exploiting this zone.

Now, all of the foregoing reasoning is a complete fucking disaster. Daniel Paleka presents at least three independent ways to see that Dwarkesh’s arguments do not work1.

I

Dwarkesh ignores the information gained in Supervised Learning when the model makes incorrect guesses:

Think about it this way: if your model is predicting “Bob’s favorite animal is” → “cat” with 50% confidence when the correct token is “dog”, do these two approaches give the same amount of information?

You learn the correct token is not “cat”. We’ve effectively gained one bit of information: we know it’s not “cat”, but it could be any other animal.

You learn the correct token is “dog”. We resolved the entire uncertainty about Bob’s favorite animal.

It’s clear the second update is much more informative than the first.

The former is what is going on with RL agents, and the latter is what’s going on with supervised models.

II

This connects to a more general conceptual confusion. You should not expect the upper bounds in the learning efficiency of RL to ever exceed that of Supervised Learning: you can throw away information to turn the latter into the former, but cannot turn the former into the latter:

…we always gain at least as much information from knowing the correct token as from knowing if our guess is correct. In other words, we can always turn supervised learning into RL by discarding information; but we cannot go the other way around.

We could formalize this via the data processing inequality, because the binary outcome is a function of the correct token given our prediction; but I don’t think it’s useful to do so here.

III

Paleka steps through an example. Assume our models are guessing on multiple choice questions, with K - 1 wrong answers. We set a uniform probability mass on these K - 1 options of:

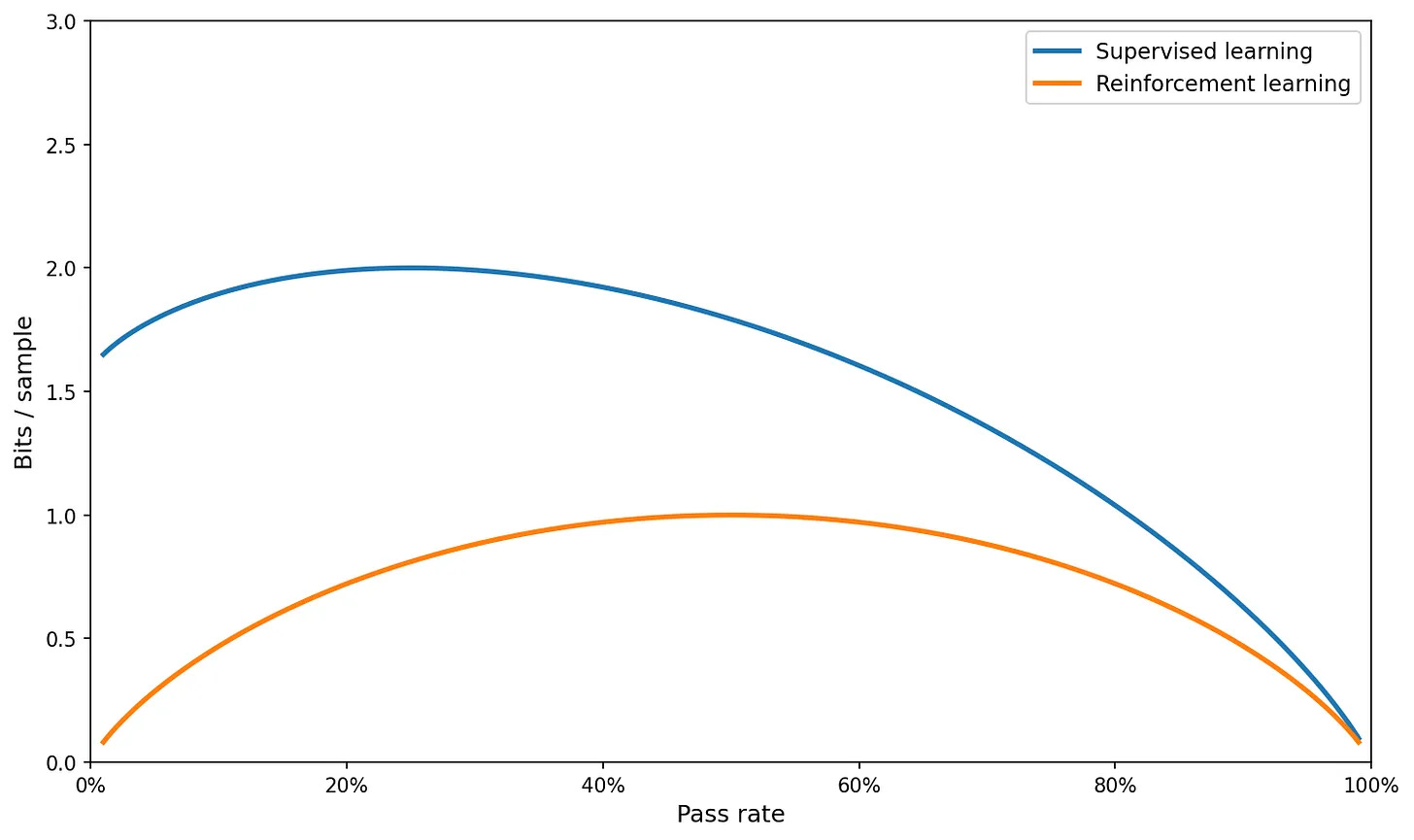

So their probabilities sum up to 1 - r. From this, we get that the sample efficiency is bounded above by:

Which for K = 4 is:

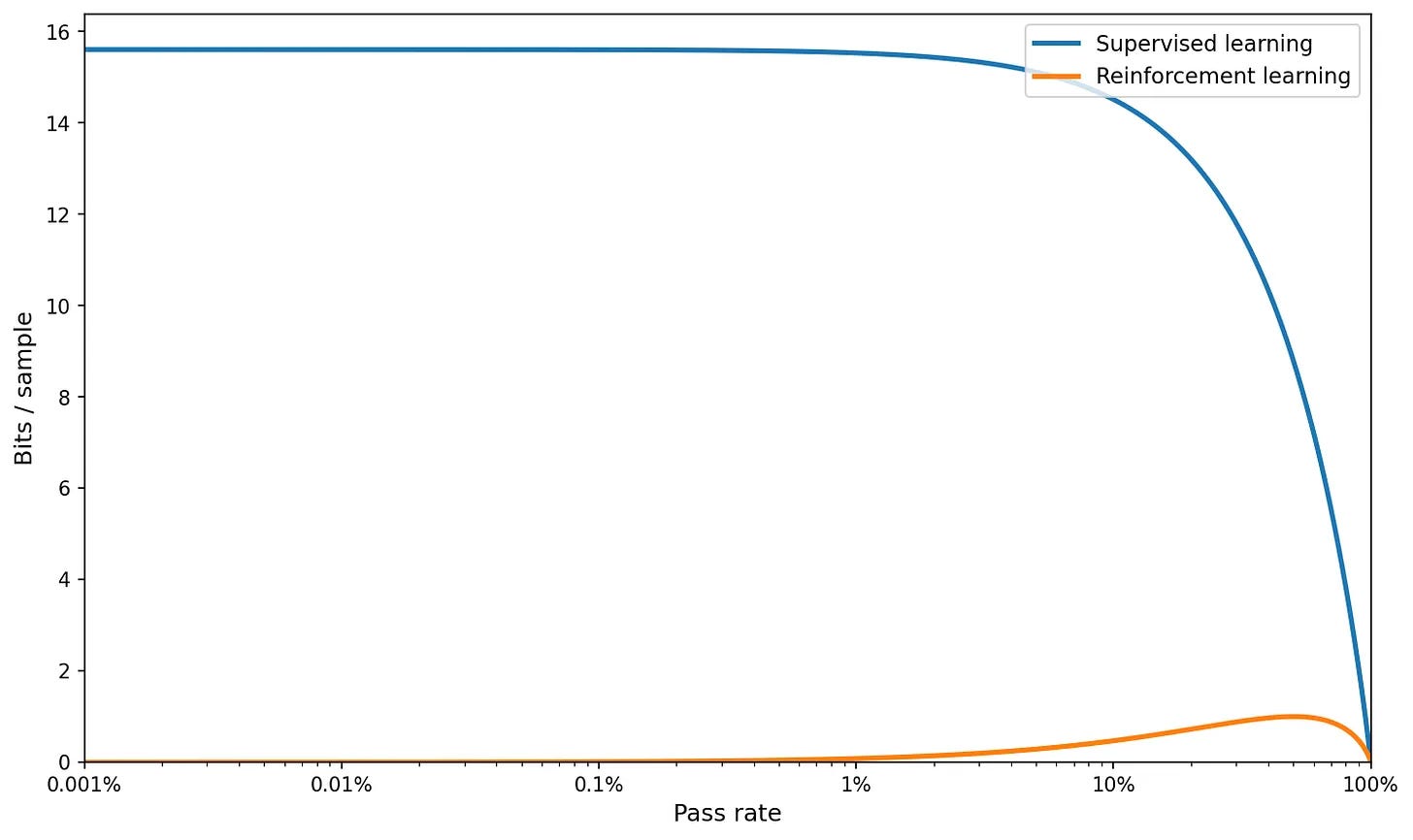

For large K and with log scale on the x-axis:

No bueno.

Where did Dwarkesh’s reasoning come from, and why was it not caught earlier? Why was it not caught by his readership?

In Dwarkesh’s recent podcast episode with Ilya Sutskever he does an ad read for Gemini 3 that explains all2:

So, I have to say that prepping for Ilya was pretty tough because neither I nor anybody else had any idea what he was working on and what SSI is trying to do. I had no basis to come up with my questions, and the only thing I could go off of, honestly, was trying to think from first principles about what are the bottlenecks to AGI, because clearly Ilya is working on them in some way. Part of this question involved thinking about RL scaling, because everybody’s asking how well RL will generalize and how we can make it generalize better.

As part of this, I was reading this paper that came out recently on RL scaling, and it showed that actually the learning curve on RL looks like a sigmoid. I found this very curious. Why should it be a sigmoid where it learns very little for a long time, and then it quickly learns a lot, and then it asymptotes?

This is very different from the power law you see in pre-training where the model learns a bunch at the very beginning, and then less and less over time. And it actually reminded me of a note that I had written down after I had a conversation with a researcher friend where he pointed out that the number of samples that you need to take in order to find a correct answer scales exponentially with how different your current probability distribution is from the target probability distribution.

And I was thinking about how these two ideas are related. I had this vague idea that they should be connected, but I really didn’t know how. I don’t have a math background, so I couldn’t really formalize it.

But I wondered if Gemini 3 could help me out here. And so I took a picture of my notebook and I took the paper and I put them both in the context of Gemini 3 and I asked it to find the connection. And it thought a bunch, and then it realized that the correct way to model the information you gain from a single yes or no outcome in RL is as the entropy of a random binary variable. It made a graph which showed how the bits you gain for a sample in RL versus supervised learning scale as the pass rate increases. And as soon as I saw the graph that Gemini 3 made, immediately a ton of things started making sense to me.

Then I wanted to see if there was any empirical basis to this theory. So I asked Gemini to code my experiment to show whether the improvement in loss scales in this way with pass rate. I just took the code that Gemini outputted, I copy pasted it into a Google Colab notebook, and I was able to run this toy ML experiment and visualize its results without a single bug. It’s interesting because the results look similar but not identical to what we should have expected.

And so I downloaded this chart and I put it into Gemini and I asked it, what is going on here? And it came up with a hypothesis that I think is actually correct, which is that we’re capping how much supervised learning can improve in the beginning by having a fixed learning rate. And in fact, we should decrease the learning rate over time. It actually gives us an intuitive understanding for why in practice we have learning rate schedulers that decrease the learning rate over time.

I did this entire flow from coming up with this vague initial question to building a theoretical understanding to running some toy ML experiments, all with Gemini 3. This feels like the first model where it can actually come up with new connections that I wouldn’t have anticipated.

It’s actually now become the default place I go to when I want to brainstorm new ways to think about a problem.

Bro is straight up raw vibethinking.

I was going to underline certain consequential sentences from this ad read, but I cannot because virtually every sentence is so potent. How the errors cascade; the feeling of revelation imparted at each step; “I don’t have a math background”; “[t]his feels like the first model where it can actually come up with new connections that I wouldn’t have anticipated”; “[i]t’s actually now become the default place I go to when I want to brainstorm”… This is a masterpiece.

What makes this error so hard to catch is a collection of characteristic features of LLM-generated knowledge. Gemini proposed to Dwarkesh a novel approach that doesn’t exist in the literature (as I said earlier, there isn’t really a formalism for “sample efficiency” that is common across machine learning methods), that is simple (so it feels nice and juicy), but fundamentally confused. This is a potent formula for false revelation.

This sort of information pollution is going to be an increasingly discourse-steering portion of the epistemic commons in the near future. One day, we will have language models that are smart and wise enough to slap us in the face when we try to unify quantum mechanics and general relativity on our smartphones, but that isn’t really the state of play now34.

Is this more “stochastic parrot”-style LLM denialism? Let’s avoid that. I don’t see the “generative AI will never figure out how to draw hands correctly”-people apologizing for their overconfidence. Vibethinking bullshit is different from hands, clock-faces, and the like. The latter track concerns about absolute capabilities, whereas the former tracks concerns about relative capabilities. The delta between human and machine knowledge is what makes us vulnerable to being sniped by fallacious vibethinking.

This brings me back to the recipe for bullshit reduction I proposed in Notes on Honesty:

Decrease the amount of bullshit you speak by:

Knowing more.

Not being put into situations where you are required to talk about something you don’t know about.

Though advancements in artificial intelligence may be demoralizing to some, and though we may live to see human researchers exiled from the technological frontier, I believe that in the short-run there is going to be a large amount of value in actually studying stuff deeply.

You can just read Daniel Paleka’s piece (and ❤️ it in any case please), but I will inline his arguments here anyways.

Again, hat tip to Daniel Paleka for pointing this out to me in conversation. The following stuff Dwarkesh says is so funny and alarming that I felt compelled to write this blog post.

Recently Scott Aaronson told me that he’s noticed a sizeable uptick in the number of emails he gets sent containing crank P vs NP “proofs”.

The Lightcone team told me that LessWrong has had to undergo a bunch of changes to its moderation guidelines and tooling to handle the influx in vibethinking posts.

Seems harsh. I love using the LLM as a rubber duck, *especially* for brainstorming, and this rubber duck talks back! Usefully, in the main. Sure it’s often subtly wrong, but then again, so am I. Dwarkesh’s sin seems to be insufficient domain knowledge to properly sanity-check the LLM’s reasoning?

The bullshit velocity is increased, and LLM BS *sounds* dangerously plausible, but in my experience at work, the actually-good-idea velocity has also increased.

Nevertheless, a valuable cautionary tale.

i saw this post, really liked it, then immediately started using chatgpt to interpret a friend's message.

vibe-thinking is suboptimal, but it's going to happen. what are the mitigation tactics / ways to make it less destructive?

i also need to think more about the RL sample-efficiency thing. feel like daniel hasn't gotten to the end of this