The Reputational Windfall

Overattributing greatness to great people

When memory decays it is sometimes possible to predict what will be lost. Sutherland & Cimpian showed that specifics tend to decay into general kinds (e.g. people struggling to remember “cheebas sleep through the winter” turn it into “all cheebas sleep through the winter”). I have observed a genericization that I have called in my head a “reputational windfall” wherein the most conspicuous member of a class gets singled out for praise for a quality that is in fact commonplace to their group. This effect seems to me particularly common when people praise great artists and thinkers whose peers have been forgotten.

I’ll offer some examples.

Thomas Aquinas

When the history of philosophy is taught in the United States, it is only a little bit of an exaggeration to say that departments jump from Aristotle straight to Descartes. In particular the Scholastics are passed over, suffering as they do from a reputation of being preoccupied with substanceless conundrums such as “how many angels can dance on the head of a pin?”. The University of Chicago — where I studied as an undergraduate — had many Augustine and Aquinas specialists in its philosophy department, resulting in an unusual amount of attention invested into studying the philosophical content of scholastic arguments. I read Aquinas’s Summa Theologica in four separate courses, and so had a fair amount of looks at seeing people encounter Aquinas for the first time. Undergraduates were typically amazed at the variety, quality, and density of Aquinas’s arguments. The Summa is written in a way that foregrounds argument above all. A typical article from the Summa is structured in the following way: Aquinas opens with three strong objections to his position; he then states his position, reinforces it with a quote from Aristotle, the Bible, or one of the Church fathers; he then explains the reasoning behind his position in detail; then he closes with counterarguments to each of the three objections discussed earlier. Here is an example:

Article 3. Whether some concupiscences are natural, and some not natural?

Objection 1. It would seem that concupiscences are not divided into those which are natural and those which are not. For concupiscence belongs to the animal appetite, as stated above. But the natural appetite is contrasted with the animal appetite. Therefore no concupiscence is natural.

Objection 2. Further, material differences makes no difference of species, but only numerical difference; a difference which is outside the purview of science. But if some concupiscences are natural, and some not, they differ only in respect of their objects; which amounts to a material difference, which is one of number only. Therefore concupiscences should not be divided into those that are natural and those that are not.

Objection 3. Further, reason is contrasted with nature, as stated in Phys1. ii, 5. If therefore in man there is a concupiscence which is not natural, it must needs be rational. But this is impossible: because, since concupiscence is a passion, it belongs to the sensitive appetite, and not to the will, which is the rational appetite. Therefore there are no concupiscences which are not natural.

On the contrary, The Philosopher2 (Ethic3. iii, 11 and Rhetor4. i, 11) distinguishes natural concupiscences from those that are not natural.

I answer that, As stated above (Article 1), concupiscence is the craving for pleasurable good. Now a thing is pleasurable in two ways. First, because it is suitable to the nature of the animal; for example, food, drink, and the like: and concupiscence of such pleasurable things is said to be natural. Secondly, a thing is pleasurable because it is apprehended as suitable to the animal: as when one apprehends something as good and suitable, and consequently takes pleasure in it: and concupiscence of such pleasurable things is said to be not natural, and is more wont to be called “cupidity.”

Accordingly concupiscences of the first kind, or natural concupiscences, are common to men and other animals: because to both is there something suitable and pleasurable according to nature: and in these all men agree; wherefore the Philosopher (Ethic. iii, 11) calls them “common” and “necessary.” But concupiscences of the second kind are proper to men, to whom it is proper to devise something as good and suitable, beyond that which nature requires. Hence the Philosopher says (Rhet. i, 11) that the former concupiscences are “irrational,” but the latter, “rational.” And because different men reason differently, therefore the latter are also called (Ethic. iii, 11) “peculiar and acquired,” i.e. in addition to those that are natural.

Reply to Objection 1. The same thing that is the object of the natural appetite, may be the object of the animal appetite, once it is apprehended. And in this way there may be an animal concupiscence of food, drink, and the like, which are objects of the natural appetite.

Reply to Objection 2. The difference between those concupiscences that are natural and those that are not, is not merely a material difference; it is also, in a way, formal, in so far as it arises from a difference in the active object. Now the object of the appetite is the apprehended good. Hence diversity of the active object follows from diversity of apprehension: according as a thing is apprehended as suitable, either by absolute apprehension, whence arise natural concupiscences, which the Philosopher calls “irrational” (Rhet. i, 11); or by apprehension together with deliberation, whence arise those concupiscences that are not natural, and which for this very reason the Philosopher calls “rational” (Rhet. i, 11).

Reply to Objection 3. Man has not only universal reason, pertaining to the intellectual faculty; but also particular reason pertaining to the sensitive faculty, as stated in [earlier articles]: so that even rational concupiscence may pertain to the sensitive appetite. Moreover the sensitive appetite can be moved by the universal reason also, through the medium of the particular imagination.

This article is pretty deep in the weeds and might strike you as obscure and uninteresting, but I just want to point at how argument-dense it is. The practice of always opening with three strong objections to your position is epistemically salutary. It definitely leaves a deep impression on someone who came to the text half-thinking that it would be stuffed full of pieties, dogma, and sophistry.

I’ve had a decade of reading Aquinas, and now I’m not so impressed with him (I discuss this a bit here). I remember ten years ago, myself and my peers would talk about Aquinas as if no other philosopher contained so much argument and counterargument, that no other philosopher was so epistemically virtuous. But the virtues we attributed to him are not exceptional to Aquinas, but rather are common to his peers. The disputation style of Aquinas’ writing (which we had never seen before, as the Greeks, the Early Moderns, and contemporary academic philosophers do not write in this way) was standard for medieval scholastic writing. The standard textbook of theology for the era was Pierre Lombard’s Sentences. It is difficult to find English translations of this work (most of the people who would want to read it already know Latin), but (apparently) it commanded more respect than the Summa for many centuries. A typical chapter of the Sentences looks like this5:

1. WHETHER ALL MEN ARE TO BE LOVED EQUALLY. And so, as to this, too, a question is frequently raised, which the various views expressed by the saints make perplexing.

2. HE SETS OUT SOME AUTHORITIES WHICH APPEAR TO SAY THAT ALL ARE TO BE LOVED EQUALLY, BUT THAT THERE IS SOME DIFFERENCE IN THE DOING OF IT. For some seem to teach that all are to be loved with equal affection; but a distinction is to be preserved in the doing of it, that is, in the manifestation of respect—AUGUSTINE, IN BOOK 1, ON CHRISTIAN DOCTRINE. Hence Augustine: “All men are to be loved equally. But since you cannot be useful to all, you are to be particularly attentive to those who, by occasion of places, or times, or any other circumstances, are joined more closely to you, as if by some destiny. For that is to be considered destiny by which someone is more closely connected to you for the time being, and by reason of which you read that you are to give more to him.” —THE SAME [AUGUSTINE], ON THE EPISTLE TO THE GALATIANS: “Let us work good to all men, but especially to those who are of the household of the faith, that is, to Christians. For eternal life is to be wished for everyone with equal love, even though the services of love cannot be shown to everyone.” These are to be shown especially to the brethren, “because they are members of one another,” “since they have the same Father.” —These are the authorities by which they, who say that all men are to be equally loved by the affection of charity, but that there is a difference in the performance of works, support their view.

3. WHAT [AUTHORITIES] SEEM TO BE IN OPPOSITION TO THESE. But in opposition to these stands the commandment of the Law concerning the love of parents: Honour your father and your mother, so that you may have long life upon the earth. For what reason would this be especially commanded concerning parents, if not because they are to be loved with a greater love?—But they say that this is to be referred to the provision of external goods, in which parents are to be placed first; that is why it says honour, and not love.

4. JEROME. In opposition to these stands also what Jerome says, in On Ezechiel, namely “that by the order of charity, as it is written: He set charity in order within me, after God the father of all, our father according to the flesh is also to be loved, and our mother, our son and daughter, our brother and sister.”

…

6. HERE IS SHOWN THE ORDER OF LOVING. See, by the foregoing the distinction which is to be kept in the feeling of charity is clearly indicated, so that we love men with a different feeling, and not an equal one, and that we love God before all, ourselves second, parents third, then children and siblings, then members of our household, and finally enemies.—But they say that the things said above about the order of love are to be referred to the performance of works, which are to be extended differently to our neighbours: to our parents first, then to our children, afterwards to the members of our household, and finally to our enemies; but God is to be loved before all in both feeling and the manifestation of respect.

...

9. DETERMINATION OF THE AUTHORITIES WHICH SEEM TO CONTRADICT EACH OTHER. But what Augustine says, that all are to be loved equally and that, with equal love, life is to be desired for everyone, can be taken in this sense: that the parity be referred not to the feeling, but to the good which is desired for them, because we must desire by charity that all deserve equal goods, as the Apostle says: I wish all men to be like me. Indeed, the perfection of their betters is to be wished for those who are less good, so that they too become perfect and so deserve an equal blessedness. Or ‘with equal love,’ that is, all are to be loved by the same love.— Also, his statement, that we love our brothers as much as ourselves, can be taken in this sense: that is, let us love our brothers for the sake of as much good as for ourselves, so that we desire as much good for them in eternity as for ourselves, even though with not as much feeling. But there ‘as much’ denotes likeness, not quantity.

Again, this might come off as obscure and uninteresting, but I want to point to how much space Lombard gives to articulating the reasons behind the position he disagrees with. It is not obvious to me that this writing is less dense in quality arguments than Aquinas’s6. But since Lombard and the rest of the minor scholastics are not read anymore, but Aquinas is still read, Aquinas gets to reap the reputation that would have otherwise been held in common.

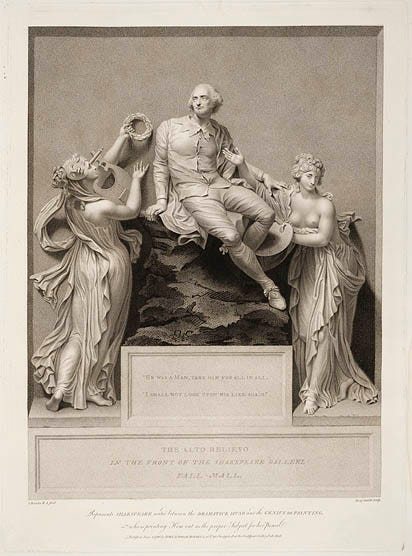

Shakespeare

I am pro-bardolatry, and definitely think that people should read a lot of Shakespeare. But I do think he benefits from a reputational windfall. I had the opportunity to act in plays by other Elizabethan/Jacobean playwrights (Ben Jonson, Marlowe, and John Ford), and since then I’ve noticed that a fair amount of Shakespeare-praise singles him out for qualities that are not particularly unique to him. For instance, I hear a lot that Shakespeare is fun to read because his “language is so complex” or that he’s “surprisingly fun and raunchy”. Jonson, Marlowe, and Ford also employ complex language and like a bit of bawdry. Some portion of the appeal of Shakespeare is, frankly, the appeal of reading English that is 400 years old and feeling good about being able to do that. It would be surprising to me if you were to read Volpone and conclude that it is obviously worse than the median Shakespeare comedy; or read Tamburlaine and think that Tamburlaine is a weaker part than the great lead roles in Shakespearean tragedy7.

TAMBURLAINE: Nature, that fram’d us of four elements

Warring within our breasts for regiment,

Doth teach us all to have aspiring minds.

Our souls, whose faculties can comprehend

The wondrous architecture of the world,

And measure every wandering planet’s course,

Still climbing after knowledge infinite,

And always moving as the restless spheres,

Wills us to wear ourselves and never rest,

Until we reach the ripest fruit of all,

That perfect bliss and sole felicity,

The sweet fruition of an earthly crown.

And so Shakespeare reaps the reputational windfall, because his contemporaries are rarely read and performed.

Other Minor Examples and Counterexamples

I run some rationality meetups, and I feel that people overattribute good vibes to me. I get thanked semi-regularly for the room and the conversations feeling good. I think but don’t say: But I didn’t do that — actually you did! If you are inclined to thank someone for how fun a group is, you probably thank the most conspicuous guy. So that’s how I reap a reputational windfall.

I don’t claim that reputation windfalls follow a law-like structure though, as there are many exceptions. I’m tempted to say that many CEOs reap the windfall too. Successful companies are hundreds of thousands of good decisions per year every year, and some CEOs make like three decision a year. People tend to synecdochize Tesla into Elon, allowing him to reap the windfall. But overall CEOs are probably underappreciated, and actually undercompensated, as Tyler Cowen argues in Big Business:

There is another lesson from the numbers: CEOs are paid less than the value they bring to their companies. More concretely, CEOs capture only about 68–73 percent of the value they bring to their firms. For purposes of comparison, one recent estimate suggests that workers in general are paid no more than 85 percent of their marginal product on average [Isen 2012]; that difference is attributed largely to costs of searching for workers and training them to become valuable contributors. In other words, workers actually seem to be underpaid by somewhat less than CEOs are, at least when both are judged in percentage terms. Both of those are inexact estimates, but in fact these results are what economic reasoning would lead us to expect. It may be easier to bargain the CEO down below his or her marginal product a bit more, given that the talents of the CEO would be worth much less in non-CEO endeavors.

I find the most convincing estimate of the gap between pay and marginal product to be that of Lucian A. Taylor, at the Wharton School of Business. He finds that a typical major CEO captures somewhere between 44 percent and 68 percent of the value he or she brings to the firm, with the additional qualification that the CEO’s contract offers some insurance value—that is, in bad times for the firm the pay of the CEO won’t be cut in proportion, but the CEO shares to a lesser degree on the upside. That 44–68 percent is therefore a better deal for the CEOs than it may appear at first glance. Still, you won’t find credible estimates suggesting that major CEOs, taken as a group, are capturing more than 100 percent of their value added. Here too, that is what you would expect from a competitive bidding process.

So our purported tendency to overpraise the most conspicuous guy is moderated or reversed by other tendencies. I only claim that this “reputational windfall” phrase has been a useful label to point at things for me, and you might also find it useful.

i.e. Aristotle

From: Peter Lombard, The Sentences Book 3 On the Incarnation Of the Word, translated by Giolio Silano.

Both the Summa and the Sentences strike me, now, as being filled with spurious arguments. Which is to say I think they are similar quality, and hence it is a bit of an injustice that Lombard and Aquinas command unequal prestige. Both selections above seem to me to suffer from the same problem. They take what seems like a contradiction between two credible views, and resolve it by inventing distinctions that are only really relevant for the specific task of resolving the contradiction. The statement in the Summa I quoted above where Aquinas states “…now a thing is pleasurable in two ways” — this is just very typical Aquinas. Lombard does a similar thing: It seems like we are enjoined to love men equally, but also to especially honor our parents; how can these two things be compatible? Well, it turns out there are different types of love that we feel with different intensities, so we can and should love our parents with high categorical intensity, but we can at the same time love everyone equally in the sense that we want everyone to ultimately receive equal goods (as in, we hope everyone goes to heaven). So it turns out there is no contradiction. Now maybe what Lombard is arguing is correct, but to my eye it transparently is motivated thinking.

I do think one conspicuous quality that makes Shakespeare superior to his peers is how substantial his minor characters are. His contemporaries do write great lead parts, but they frequently share company with many thin, functional, utilitarian minor characters. With Shakespeare, there are many flavorful and substantial small parts that a downbill actor could really make hay out of. For instance with Hamlet: look at the characters of Barnardo, Marcellus, the First Player, the Gravedigger and see how much personality they have.

Regarding your meetup role, you are being overly modest. You often choose the readings, frame the discussion, and are clearly monitoring the flow and intervene to course correct when necessary. This adds value and unlocks value, so the appreciation and acknowledgment is well deserved.

Thought provoking, and I imagine it might be interesting to explore the negative impacts of these misattributions in various scenarios. And perhaps, what we might do differently, and what could be gained in doing so. If you have any thoughts on that, I’d be interested to read a follow-up post about it.